Crossed Hatchets and Detached Service: The Creation of the Pioneer Brigade

By The LR Research Committee

Few units on either side of the American Civil War can claim to be as unique in structure and character as the Army of the Cumberland’s Pioneer Brigade. They were an amalgamated unit that was formed in November of 1862. Their title appears self explanatory but in order to fully understand the role and significance of the unit, one must first gain a better understanding of pioneers in the early days of and leading up to the Civil War.

The Pioneer has long been an established rank within the U.S. Regular Army, however, these pioneers, only amounted to a negligible segment of the regular army population prior to the Civil War. Nonetheless, engineering and pioneer soldiers played an important part in the American military since its beginning. When describing pioneers, Article 21 of the 1821 Army Regulations reads as follows:

Selection of pioneers

1. Intrepidity, strength, and activity, are the qualifications which will be considered the most necessary for pioneers, who will be nominated and put in orders in the manner prescribed for company non-commissioned officers. The colonel will select one of the corporals of the regiment to command them when embodied (1).

Rank and function of a pioneer soldier date from well before the establishment of the American military. But for our purposes, at the beginning of the Civil War, the Pioneer was simply a rank in the Regular Federal Army. Though often considered a classification of engineer troops, the pioneer’s branch of service could vary, as designated by the 1861 Regulations, which account for variations in insignia, dependent on the “edging of the collar” (2).

In conjunction with these few pioneer soldiers scattered among regular army units and far flung military posts, there was a contingent of Engineering officers and soldiers. In 1861, the engineers of the U.S. Army were divided into two branches, the Corps of Engineers and the Topographical Engineers. Together, these two branches were composed of ninety-three officers and one company of soldiers (3). The best candidates from West Point were usually selected for these branches. During the Civil War, many transferred or assumed positions, which superseded their duties as engineers. Needless to say, logistics and engineering were in short supply when the Confederates fired on Ft. Sumter.

When the Civil War caused a need for volunteer troops, these engineers and pioneers were not enough to go around. In turn, the hurried organization of volunteer troops often overlooked logistical support. Volunteer regiments, some of them only recently upgraded from informal militias, were to serve as combat infantrymen, cavalry, or artillery. Often, the only appearances of engineering officers were those who filled general staffs and other logistical positions.

But that did not exclude these volunteer troops from pioneer duties and engineer work. Though they were often ill equipped for it, the volunteers still faced the same logistical nightmares that every army has faced. But pioneer labor and similar tasks were treated as any other obligation of the army. Soldiers were detailed for pioneer work, just as they were detailed for guard. Phillip Shiman explains, “Pioneers were soldiers or laborers assigned to perform mundane tool work or tasks of immediate, tactical importance to the army, such as, repairing roads, clearing obstructions, and building small bridges.” These duties covered everything from simple afternoon fatigue duty to brief detached service from a company or regiment in order to complete larger, more pressing tasks. This pragmatic approach to logistics and the scarce engineering troops quickly proved inadequate.

Figure 1: Rosecrans as a young engineering officer.

A few engineering units were recruited as volunteers. These units included New York’s 1st, 15th, and 50th Engineer Regiments (the latter designated Sappers, Miners, and Pontonier’s), along with the 1st Michigan Engineers and Kentucky’s “Patterson’s Independent Company.” These engineer units and a few others were created in the fall of 1861. But with the growing enormity of military operations, even this was not an adequate solution.

In the western theater these problems were especially obvious. There the army’s supply lines often stretched hundreds of miles and the challenging terrain only served to exacerbate the problems. But in the fall of 1862, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans took command of the Army of the Cumberland. He was well versed in military engineering and not only served in the Corps of Engineers after graduation from West Point, but returned to the Academy in 1843 to spend two years teaching engineering. With a solid engineering foundation, Rosecrans envisioned a solution to the problems facing his army. There were not enough engineering officers or enlisted soldiers in the regular army to solve the problem. The solution would have to come from the troops he already had at hand. He imagined a larger and more systematic approach. So, on November 3, 1862, he issued General Orders No. 3:

There will be detailed immediately, from each company of every regiment of infantry in this army, two men, who shall be organized as a pioneer or engineer corps attached to its regiment. The twenty men will be selected with great care, half laborers and half mechanics. The most intelligent and energetic lieutenant in the regiment, with the best knowledge of civil engineering, will be detailed to command, assisted by two non-commissioned officers. This officer shall be responsible for all equipage, and shall receipt accordingly.

Under certain circumstances it may be necessary to mass this force: when orders are given for such a movement, they must be promptly obeyed.

The wagons attached to the corps will carry all the tools, and the men's camp equipage. The men shall carry their arms, ammunition, and clothing.

Division quartermasters will immediately make requisitions on chief quartermasters for the equipment, and shall issue to regimental quartermasters on proper requisition.

Equipment For Twenty Men - Estimate For Regiment

Six Felling Axes

Six Hatchets

Two Cross-Cut Saws

Two Cross Cut Files

Two Hand-Saws

Two Hand-Saw Files

Six Spades

Two Shovels

Three Picks

Six Hammers

Two Half-Inch Augurs

Two Inch Augurs

Two Two-Inch Augurs

Twenty lbs. Nails, Assorted

Forty lbs. Spikes, Assorted

One Coil Rope

One Wagon, with four horses, or mules

It is hoped that regimental commanders will see the obvious utility of this order, and do all in their power to render it as efficient as possible (4).

This order took many soldiers away from their companies and sent them to train near Nashville. Whether by chance or Rosecran’s design, it was not completely understood by all officers that their men were to be permanently detailed to the new brigade. This avoided the problem of the brigade becoming a dumping ground for a company’s shirkers and jonahs. George W. Morris of the 81st Indiana describes his observations on General Order No. 3:

In the latter part of 1862 while the army lay at Edgefield, Tennessee, there was an order issued by General Rosecrans to form what was called the Pioneer Corps... Their work was to build bridges, railroads, cut roads through the cedars for the ambulances, and everything else that the army had to do. A number of times they were fighting like the balance of the army (5).

Figure 2: James St. Clair Morton upon being promoted to Brig. General in 1863

Still, the pioneers of the brigade were exempt from the mundane duties of guard and basic fatigue work. Captain James St. Clair Morton was charged with organizing the new unit. He had graduated West Point in 1851 and served as an assistant engineer during work at Ft. Sumter. Since May 1862, he had supervised the Army of the Ohio’s, First Michigan Engineers.

When first formed, the structure of the Pioneer Brigade was established to operate either together or as three separate wings in relation to the three wings of the main army. The First Battalion of the Pioneer Brigade was composed from the 14th Corps or center wing. The Second Battalion came from the right wing or 20th Corps. The Third Battalion was from the left and 21st Corps (6). Geoffrey Blankenmeyer describes their unit organization further:

Each battalion was subdivided into ten to twelve companies of eighty to one hundred men aggregated into four or five regiments. These battalions were organized to work independently of each other further economizing their efforts. Because the size of the brigade sometimes exceeded five thousand men, it was often referred to as the Pioneer Corps. Even official reports vary in their identification of the Pioneers. However, unofficial unit records most often identify it as"Brigade" . . . (7)

Rosecrans firmly believed that this would greatly help the problems facing his army. Though basically a conglomeration of men from the entire army, they were quickly treated as a cohesive organization. Morton established a staff of majors and adjutants even though the officers’ detail was officially only comprised of Lieutenants (8). The Brigade was to function quickly and efficiently and all aspects of their organization reflected this.

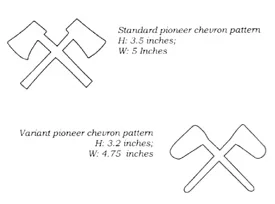

It seems difficult to discuss the pioneers without discussing their distinctive insignia as seen in Image 3. According to the U.S. Army Regulations, the rank was identified by crossed hatchets, described as follows:

For a Pioneer: Two crossed hatchets of cloth, same color and material as the edging of the collar, to be sewed on each arm above the elbow in the place indicated for a chevron (those of a corporal to be just above and resting on the chevron,) the head of the hatchet upward, its edges outward, of the following dimensions, viz.: Handle- four and one half inches long, one fourth to one third of an inch wide. Hatchet - two inches long, one inch at the edge (9).

Though these instructions are very specific, their are several images of and surviving examples, many of which vary (compare the two styles in Image 3).

Figure 3: Pioneer chevrons.

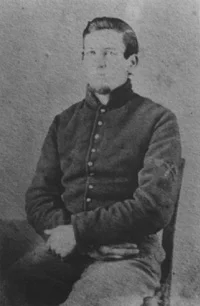

Figure 4: Pvt. William Perkins of the Pioneer Brigade’s 3rd Battalion sports pioneer chevrons. Note his chevrons are applied directly to the jacket.

In regard to the Army of the Cumberland’s “Pioneer Brigade," the chevrons worn were surprisingly not light blue. In fact, “. . . in the case of the Army of the Cumberland, infantry pioneers wore the device in yellow – the branch of service color designating engineers – not blue, the branch of service color for infantry” (10). In 1863, Isaac Raub of the Third Battalion, Pioneer Brigade references their insignia; “We wear a badge on our left arm. The badge has two hatchets on it and that badge is the same as a pass. We can go anywhere and the guards don’t trouble us any” (11).

At the beginning of December, the Pioneer Brigade left Nashville and rejoined the Army of the Cumberland, in time to participate in the winter campaign of Stones River. Conflicting marching orders surrounded the Christmas holiday. But following Christmas day, the army began to move. Sergeant Henry V. Freeman of the Third Battalion, Pioneer Brigade describes the march, "10 P.M. - Marching orders for 6 o'clock. There was no mistake about it this time. ...reveille sounded at 4 o'clock." 1600 of the 2600 men in the Pioneer Brigade participated in the march to Murfreesboro.

The Pioneers were engaged in building fords and clearing roads in the days before Murfreesboro. But soon, on December 31st, 1862 the battle of Stone's River or Murfreesboro began. Though they spent earlier parts of the engagement in the Union rear, they soon had a chance to distinguish themselves on the battlefield.

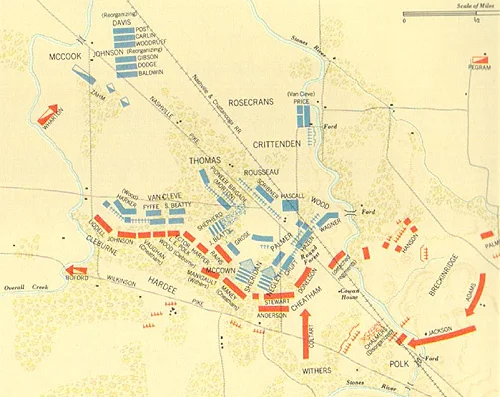

Fighting bravely near the Union center and alongside the Chicago Board of Trade Battery (Image 5), the Pioneer Brigade was crucial in staving off the Confederates while much of the army rallied itself (Image 6). Though infantry duties were its secondary purpose, in this battle the brigade first distinguished itself as fighting men.

Figure 5: The Chicago Board of Trade Battery at Murfreesboro, Tn.

Figure 6: The Battle of Stones River, where the Pioneer Brigade distinguished itself in battle.

For a brief time, the Pioneer Brigade was a successful endeavor. They spent the months following Stone’s River constructing the nearby Fortress Rosecrans. During that time and subsequent campaigns, the Brigade completed a variety of tasks. They built fortifications, bridges, fords, repaired railroads and all manners of other duties. They also spent time operating as an entire brigade and as independent battalions or even smaller details.

Figure 7 : Federal Heavy Artillery Pioneer – 1866.

But for all of their success, the Pioneer Brigade had its problems. Because of their detached status, soldiers were often still on their original unit rosters. This created complications with pay and equipment issues. In contrast to their laudable work in the field, the brigade created a reputation that was less than positive. Shiman writes, “While the Pioneers performed well enough when concentrated for engineer work under Morton's watchful eye, they did particularly badly when scattered on pioneer duty with the army. During the march to Tullahoma during the summer of 1863 their behavior was a minor scandal. They did little drilling and at times there was much drunkenness" (12).

The Pioneers spent most of their last months in Nashville working on railroads and forts, as needed. They were disbanded in September of 1864, as a casualty of the argument over how engineering and pioneering duties should be addressed with the army. Still, many of the Pioneer Brigade members were recruited into the 1st U.S. Veteran Volunteers Engineers. Many of the duties that the pioneers had performed returned to the realm of company and regimental commanders but the 1st USVVE served in the more advanced engineering duties that the Pioneers were responsible for.

The Pioneer Brigade was an important step in addressing the problems that faced a growing and mobile army. Even if they did not outlast the war, the experiment that was first attempted by Rosecrans would influence the decisions of later commanders. For example, General Meade issued General Order No. 15 for the Army of the Potomac in April of 1864, which read as follows,

II. The following is established as the organization and equipment of the pioneer parties of this army: First. The unit of organization will be by brigade. In each brigade 1 man shall be selected for every 50 men equipped for duty in it; for every ten men thus selected a corporal shall be detailed and for every 20 a sergeant, and for each brigade 1 lieutenant. . . . They will be excused from all guard and picket duty and ordinary fatigue details . . . On the march, they will move at the head of the infantry column and promptly put in order all parts of the route . . . (13)

Though not entirely the same, this structure is incredibly similar to Rosecrans’ earlier attempt. No longer could pioneering duties be assumed. Commanders realized the inefficiency of previous methods of tackling these problems. The Pioneer brigade and subsequent efforts showed the need for change. The Pioneer Brigade provided invaluable service, but more importantly, lasting lessons for the evolving military during and after the American Civil War.

Figure 8: Garret Larew – 1st Battalion, Pioneer Brigade. Taken 1863

Figure 9: Unidentified Pioneer. Notice his variation chevrons – the triangular axe head is less widely represented in original examples.

Footnotes

U.S. Army. General Regulations for the Army, or, Military Institutes. Phila: Carey, 1821. p. 355. UB501RareBook.

Regulations for the Uniform and Dress of the Army of the United States 1861. General Orders, No. 6, 111. 13 March 1861.

Shiman, Phillip L., Engineering and Command: The Case of William S. Rosecrans 1862-1863: in The Art of Command in the Civil War, edited by Steven E. Woodworth, University of Nebraska Press, 1998. p. 85.

General Order No. 3, Headquarters, Fourteenth Corps, November 3, 1863, OR 20, pt. 2:6-7

Morris, George W., History of the 81st Indiana Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865. Franklin Printing Co., 1901.

Blankenmeyer, Geoffrey L., The Pioneer Brigade. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170702193619/http://www.thecivilwargroup.com/pioneer.html>.

Blankenmeyer, Geoffrey L., The Pioneer Brigade. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170702193619/http://www.thecivilwargroup.com/pioneer.html>.

Shiman, Phillip L., Engineering and Command, p. 92.

Regulations for the Uniform and Dress of the Army.1861.

McElhinney, James L.,”Manual for the Instruction of Civil War Pioneer Troops.” Bent, St. Vrain & Co., 2004, p. 18.

Nesbitt-Raub Family Papers. Letters home from Private Isaac Raub to his wife, Mary Jane Raub; Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks.

Shiman, Phillip L., Engineering and Command, p. 94.

General Order 15, Headquarters, Army of the Potomac, April 5, 1864, II.

Image Credits

The Generals of the American Civil War, <http://www.generalsandbrevets.com>.

The Generals of the American Civil War, <http://www.generalsandbrevets.com>.

McElhinney, James L.,”Manual for the Instruction of Civil War Pioneer Troops.” Bent, St. Vrain & Co., 2004.

Blankenmeyer, Geoffrey L., The Pioneer Brigade. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170702193619/http://www.thecivilwargroup.com/pioneer.html>.

Blankenmeyer, Geoffrey L., The Pioneer Brigade. <https://web.archive.org/web/20170702193619/http://www.thecivilwargroup.com/pioneer.html>.

Echoes of Glory: Illustrated Atlas of the Civil War. Alexandria, Va. Time-life. 1998.

Army Quartermaster Museum, <https://web.archive.org/web/20090827010705/http://www.qmmuseum.lee.army.mil/1866uniform/>.

Larew, Karl. Garret Larew Civil War Soldier with an Account of His Ancestors and of His Descendants. Baltimore: Gateway Press, 1975. p. 277.

Courtesy of Matt Caldwell.