Part 3: Advanced Studies

Jump to:

Introduction to Part 3

Part 3 of this presentation will step somewhat beyond the 15 jackets compared in the study group to explore the context in which they were produced as well as delve further into the details of their construction and the materials used. The topics and level of in depth discussion is presented as a sort of “Advanced studies” course in the Richmond Clothing Bureau’s operations and the jackets it produced.

The focus will be on four areas: fabrics – “thread counting”, etc.; stitching (by hand & by machine) and thread; buttons and buttonholes; and variations in construction. First, using available documentary evidence and comparisons of original examples from the study, the fabrics used in garment production, their characteristics and the sources from which they were procured will be presented. This will both illustrate how the RCB’s supply line for uniform fabric changed over time and the variable nature of the cloth used.

The sewing methods used by the pieceworkers who assembled the garments provides some insight into variability in the way this part of the process may have functioned. As has been noted in Part 2, both hand and machine sewing were employed although the presence of the latter calls into question (or at least modulates) the classic assumptions about who these assembled garments. The thread used in sewing and the sources from which it was obtained will also be discussed.

In addition to fabric for uniform production, the button procurement appears to have been a critical supply issue for the RCB. The diverse variety of types and large volumes sourced is a little discussed aspect of the clothing Bureau’s supply chain. Multiple suppliers, both domestic and imported, were engaged. The impact of mid-war contracts to produce a steady stream of millions of wooden buttons for the RCB needs is considered through documentary and photographic evidence as well as through actual examples including the ones in the study group. As a counterpoint to buttons, the corresponding part of the assembly process, making the button holes, will be illustrated by comparing those seen in various jackets.

Finally, a “deep dive” will be made into two additional areas where construction variations or “anomalies” are typically noted among the study examples to seek further insight into the production “process” at the RCB.

The presentation will conclude with final thoughts on the RCB and observations on what learnings have been gained.

Fabrics for Uniform Production at the RCB

The Richmond Clothing Bureau contracted for fabrics (woolen and cotton goods) for use in garment production.

Contracts with domestic mills and imports through the Blockade made up the primary sources for the fabrics they used

Domestic mills, mostly in Virginia, provided both cotton and woolen fabrics.

The Quartermaster often procured the raw materials and provided them to the mills for use in production.

Scarcity of raw wool was a major hindrance to production particularly after closing of the Mississippi river in mid 1863.

Fabric was run through the Blockade starting in 1861 and grew in volume as the war progressed

Early Government procurement was through the activities of various Confederate agents in England.

Starting in late 1862 the Quartermaster Dept. established a purchasing officer in England specifically to contract for its supply needs (including fabrics).

The Shipping Book, Richmond Clothing Depot, 1863 – 1865 is a surviving Confederate ledger in the National Archives which details the supplies including fabrics received daily by the RCB between 1 October 1863 and 30 March 1865.

Fabric shipments received were recorded by source (mill or foreign shipper), generic type (“woolen goods), and description (width, number of yards, at times color and occasionally descriptive name, e.g. “jeans”, “flannel”, etc.)

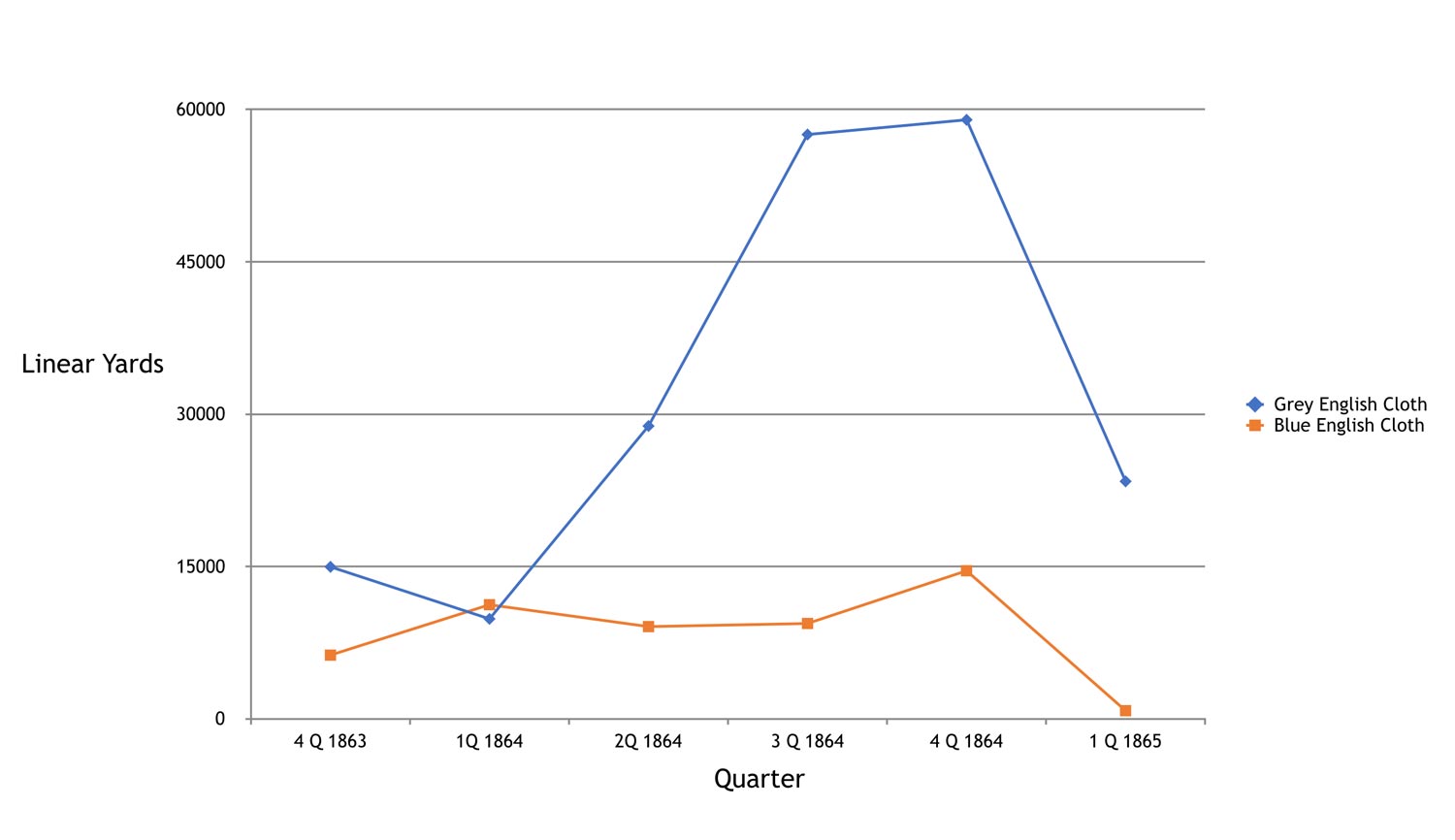

The following charts show the quantity (linear yards) of “woolen goods” received each quarter from October 1863 until the end of March 1865

For purposes of comparison 3/4 width domestic fabric yardage is converted to the 6/4 equivalent amount.

The RCB obtained the fabrics they used in garment production from multiple sources. Early in the war much of the fabric was purchased in lots from Virginia and deep south mills as well as from commercial sources like Richmond dry goods merchants. At the same time limited amounts of English fabrics came through the Blockade for Government use, starting as early as the fall of 1861. Cotton fabrics used for soldiers underclothing (shirts and drawers) as well linings in jackets and trousers were also purchased on the open market at this time.

As demands upon production increased, the RCB began contracting with local mills to insure a steady supply of bulk fabric. By late 1862, it had standing contracts with large mills in Virginia to satisfy its requirements. Generally, the government provided the mills with raw wool, cotton “warps” (the length-wise cotton yarns used to weave all “wool on cotton” fabrics), and dyestuffs needed for production. This reflects the effect of growing scarcity of certain raw materials, especially fleece wool, due to Federal incursions in western Virginia and the closing of the Mississippi north of New Orleans which limited shipments to the east from Texas. After mid-1863, with the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson, ended the flow of western wool. Further complicating the supply situation was the burning of Richmond’s Crenshaw mill in May 1863 reducing mill capability in the Virginia region. Prior to its destruction, this mill was a major supplier of woolen goods and blankets to the RCB. In the first four months of 1863 surviving Crenshaw invoices document RCB receipt of 16,980 yards of (6/4) wool/cotton fabric from their mill (sources: Kelly, Tackett, & Ford and Crenshaw Co. records, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-1865, RG 109 NARA).

In an April 1863 report to CS Quartermaster A.C. Meyers, Maj. Richard Waller, the RBC commander, acknowledged difficulties in raw wool procurement and suggested increasing woolen fabric importation from England to meet projected Army needs in the coming year. In late 1862 Meyers established a purchasing agent (Major James B. Ferguson) in England. Ferguson contracted with 16 different mills for purchase of woolen fabric and blankets. By July 1863 large shipments of English woolens were reaching Richmond for uniform production.A fascinating “window” into the flow of fabrics to the RCB during the second half of the war is provided in a ledger book found in the National Archives. The Shipping Book, Richmond Clothing Depot, 1863 – 1865, records all supplies shipped to the Bureau between 1 October 1863 and 31 March 1865. Entries range from tanned hides to bulk fabric to thread and buttons to finished goods like English shoes and blankets. Fabric shipments were listed by originator (mill or foreign shipper); type (e.g. “woolen goods” or “cotton cloth”); and a description (number of bales or pieces, linear yards, width, and occasionally color and/or a descriptive name, e.g. “jeans”, “flannel”, etc.). As the period which this ledger covers represents one when the RCB operations were relatively mature and the supply chain was under significant flux it reflects its capability to successfully adapt to the environmental challenges it faced. The following charts present the flow of domestic and imported (English) woolens for use in uniform production at the RCB. They illustrate the volumes (linear yards) of the various types of fabric received in the last six quarters or the war period.

Domestic “woolen goods” received by Quarter at the Richmond Clothing Bureau 1 October 1863 through 1 April 1865 (in linear yards)

Source: The Shipping Book, Richmond Clothing Depot, 1863‑1865, NARA RG 109

As the war entered 1864, the combination material shortages (e.g. raw wool), manpower shortages resulting from the Conscription Act, and Federal incursions into Confederate areas (particularly the Shenandoah Valley) had an increasing impact on production levels of domestically produced “woolen goods” for the RBC. However, this is not the whole story because the rising levels of English “Army cloth” being run through the Blockade as the year progressed may have significantly diminished the need for domestic material given relatively fixed capacity at the RBC. That is, they may not have required prior levels of domestic uniform cloth as they were receiving most of what they could use from English sources.

Most of the mills in the Virginia region that supplied the RCB only had the capability to produce 3/4 material which was 27” wide (i.e. 3/4 of a yard). Crenshaw Mills, before its destruction, was the major producer of “broad loomed” 6/4 (54”) material in Virginia. Based upon the records in The Shipping Book, two other mills: Kelly, Tackett & Ford of Manchester and J.B. Pace of Danville produced limited quantities of 6/4 fabric. For purposes of comparison with the volume of English “goods” received (all of which were 6/4), the 3/4 yardage was converted to the “equivalent” in 6/4 width by dividing it by 2 and combining that with the actual 6/4 domestic yardage to yield the “equivalent” 6/4 yardage total.

English 6/4 width woolen material received by Quarter at the Richmond Clothing Bureau 1 October 1863 through 1 April 1865 (in linear yards)

Source: The Shipping Book, Richmond Clothing Depot, 1863‑1865, NARA RG 109

While some English fabric for uniform production was being run through the Blockade in 1861 and 1862, beginning in the middle of 1863 very significant amounts of this material began flowing to the RBC and continued through the remainder of the conflict. This chart shows the amount of both “blue-gray Army cloth” and “light blue Army cloth” received each quarter between the end of 1863 and the first quarter of 1865. The blue material was specifically used for trouser production. In the fall of 1863, Major Ferguson in England was instructed to procure 1.2 million yards of cloth for uniforms with half being for blue for uniform pants (Source: Wilson, Harold S, Confederate Industry – Manufacturers and Quartermasters in the Civil War). However, by the fall of 1864, the flexibility of using blue gray EAC for both jackets and pants led Alexander Lawton, CS QM to instruct Ferguson to discontinue purchasing blue material stating that the “the grey makes up to more advantage” (Source: Letter from Lawton to Ferguson 24 September 1864, Official Records of the War of the Rebellion). Nevertheless, through the last two quarters of 1864 the RBC received sufficient blue English fabric for between 15% and 25% of the trousers produced.

As can be seen the amount of the blue gray fabric received at the end of 1864 was huge. This probably suggests that the vast majority of RD type III jackets produced were made from this type of material, a fact which is empirically verified by both the examples in the study and all other type IIIs that have survived. The notable drop in the amount of “English goods” received in the first quarter of 1865 corresponds to the closing of the port at Wilmington, NC in January of that year. The residual receipts (25,000 yards) probably represent “pipeline” shipments and perhaps some supplies received from other sources (i.e. other depots and state supplies transferred to the Government).

Total equivalent 6/4 width “woolen goods” received by Quarter at the Richmond Clothing Bureau 1 October 1863 through 1 April 1865 (in linear yards)

Source: The Shipping Book, Richmond Clothing Depot, 1863‑1865, NARA RG 109

This chart shows the mix of sources of fabric (domestic and English) received by the RCB over the last six quarters of the war. Two points can be made. First, the dramatic change in the sources from domestic to English that occurred during the first half of 1864 can be seen. Second, it is noted that until the flow of goods through the Blockade was curtailed by the fall of Wilmington, the supply of fabric for uniform production reached the highest level for the entire period in the last two quarters of 1864.

Generally, over the period covered in The Shipping Book, the average number yards of 6/4 (equivalent) fabric was approximately 80,000 yards each quarter. This roughly equates to 10,000 “suits of clothing” (jacket and pair of trousers) produced every month during the last six quarters of the war.

What was English “Army Cloth”?

English “Army Cloth” is the period term for woolen uniform fabric brought through the Blockade for uniform production

CS purchasing agents contracted for wool material from different mills in England between 1861 and early 1865

“Gray,” “Blue-Gray,” and “Light Blue” are most frequent color descriptions in The Shipping Book

EAC was 6/4 (54”) wide and was supposed to be 22oz to 24oz (per yard) in weight

From a fabric analysis, the “kersey” fabric in the Thomas H Tolson jacket was:

Made from “S” twist, 2 ply yarn that was “dyed in the wool” i.e. spun from a mix of blue, gray, and white dyed fibers to form a blue gray color

There were “34 to 36 (yarn) threads per inch for both the warp and the fill”

It was woven as “2/2 twill with a 45 degree angle to the twill line”

After weaving the fabric was “fulled so there are no open spaces between the yarns…napped on both sides (so that) the weave not visible” and “sheared close to the fabric”

Not all of what is called “EAC” was “kersey.” Different weaves and varying quality (lighter weight, poorly fulled and more lightly napped) fabric was received and used.

Fabric of 2/1 and 3/1 twill and “tabby” (plain) weave is seen in Richmond products

Thread count (threads per inch) varies as well

Different mixes of the colored fibers produced different (lighter/darker, more/less blue) shades of “blue-gray”

Regardless of weave or thread count, yarns from which it is woven are very similar in composition characteristic of English goods

The examples in the study illustrate that sturdy, blue gray, all wool fabric run through the Blockade from England was used in the RBC to produce enlisted men’s uniforms through most of the war. Such fabric at the time was referred to as English “Army cloth” in Quartermaster Department reports and other contemporaneous documents. James Ferguson and other CS agents purchased hundreds of thousands of yards from mills in Manchester and elsewhere in England, much of which ended up being shipped to Richmond as illustrated in the previous slides. Notations in The Shipping Book often describe the color of the material as “gray” or “blue-gray,” and “light blue” but other descriptions appear occasionally such as “oxford gray” or, rarely, “cadet gray” and “sky blue” along with simply “blue”. While such descriptors could indicate distinctions between different hues they also may simply be different clerks’ interpretation of what they saw. From period contracts, this fabric was supposed to be 6/4 width and weigh between 22 ounces and 24 ounces per yard.

A fabric analysis done by the Maryland Historical Society’s staff of the material used in the Thomas Tolson jacket indicated that the yarns were “dyed in the wool”, that is, spun from a mix of blue, gray, and white colored fibers which yielded the characteristic “blue- gray” hue. This dying technique dates to before the Middle Ages and was characteristic of English processing known to produce the most color fast results. The fabric in the Tolson jacket had 34 to 36 threads per inch and was woven in a 2/2 twill that produced a 45 degree “twill line” that is distinctive of so called “kersey” material. After weaving the material was finished by “fulling” (to shrink and tighten the cloth) and “napping” (to obscure the weave pattern). Finally, it was closely “sheared” to reduce the “fuzziness” left after “napping” and produce a tight, even surface. These are rather elaborate operations which produce a high-quality product.

Not all the English “woolen goods” were of the same quality, however. Nor, as is seen in examples in the study, was it all “kersey” weave. Different weights of fabric, differently woven and, sometimes, much more poorly (and cheaply) finished is observed among the jackets. The blue gray color also varies to some degree depending upon the mix of the blue, gray, and white fibers. The final result could initially have been lighter or darker and have a more or less blue shade in different batches from different suppliers. It is also important to realize that the color observed today in original jackets usually isn’t reflective of their original shade either as most have been altered to a great degree by dirt, smoke, and other contaminants from use and the passage of time. Close observation of selected areas in seams or where otherwise protected often shows the original color to be brighter and more vibrant.

What then, identifies EAC to be English “Army cloth?” Regardless of thread count, weave, weight or finish, the yarns from which it is woven are very similar in composition and characteristic of English production. In the following slides some attempt will be made to explain how they are similar as well as how they are different.

Early use of English “Army Cloth” in Richmond uniform production – Excerpt from a letter from Col. David Wyatt Aiken, 7th S.C. Volunteer Infantry to Lt. Col. Elbert Bland while he was recovering at home in Edgefield following his wounding during the Seven Day’s Campaign around Richmond. It is This letter is in the possession of Bland’s great**granddaughter, Mary Wallce Day.

“H’qts 7th S.C. Regt, Aug 19 1862 {8 miles east of Richmond}:

...Our conscripts are tolerably well fixed for camp life, nicely equipped & when we get our new uniform, I think the old 7th will astonish her neighbors. We are having a uniform made in Rich at the Govt rooms, dark steel mixed jacket with light blue pants. The pants are to be lined throughout with osnaburys. Both cloths are heavy & good, English manufacture. Some of the men in the Regt are opposed to it, but I forbade the Qt Mast [quartermaster] paying out a cent of clothing money, & hence they must come in...”

It is often portrayed that EAC only was used in late war products from the Richmond Clothing Bureau. This excerpt from a letter written by Col. David Wyatt Aiken of the 7th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry to his second in command, Lt. Col. Elbert Bland documents its use by the RCB for both jackets (gray) and trousers (blue) in the summer of 1862. This was during the so called “Commutation” period before the Quartermaster Department formally became responsible for providing enlisted men’s clothing. As such, the letter also confirms that the RCB was making uniforms for specific regiments at their officers’ direction in exchange for the Commutation payments due the soldiers under that system. Jensen documents a situation where special trim was approved for another regiment at the commanding officer’s request. It is not known when the 7th SC received their new uniforms but given the date of the letter it is certainly possible they may have received them before Fredericksburg if not Antietam.

Characteristic composition in English Army Cloth

“dyed in the wool”, “fulled so there are no open spaces between the yarns…napped on both sides (so that) the weave not visible” -Textile Analysis of Tolson jacket MdHS

These three closeup photographs provide an idea, visually, of what the characteristic composition of English Army cloth run through the blockade during the Civil War was like. Significantly, one is of the fabric used in 1862 (Haines jacket), a second from an 1863 example (Bryan jacket), and a third from 1964 (Knight jacket). These pictures were taken in protected locations (inside seams, hidden areas, etc.) to as close as possible show the original surface of the fabric. The 1862 and 1864 samples are from heavy weight, “kersey” weave EAC. The sample from the Bryan jacket (1863) is from relatively light weight fabric woven in a 3/1 twill not the 2/2 twill characteristic of “kersey”. Close inspection shows differences in the fabrics. Specifically, the individual stands of yarn can be seen in the Bryan sample while the effect of fulling and napping to tighten space between the strands and hide the weave in the Haines and Knight samples is also seen. Saving cost through reduction in processing and finishing (fulling, napping, and shearing) may have led to variation in quality of some “woolen goods” (perhaps supplied by unscrupulous English contractors) that were imported for Confederate use. However, what is consistent is the composition of the yarns themselves. The mix of differently colored wool fibers that create the final hue of “blue-gray” in the finished cloth is visible in each. This is the result of mixing fibers “dyed in the wool” when the yarn was spun before being woven into cloth.

John J Haines jacket, 1862 – heavy weight “Kersey” weave

George Pettigrew Bryan jacket, 1863 – light weight non “Kersey” weave

Lewis K Knight jacket, 1864 – heavy weight “Kersey” weave

Another illustration of the variations found in EAC used in RDC produced jackets is seen in the pictures below. As was pointed out earlier, the English cloth coming through the Blockade exhibits different weave patterns. The “kersey” fabric was woven in a 2/2 (“two over two”) twill pattern. Such weaving produces a distinct diagonal “wale” or 45-degree angle twill line that is characteristic of that type of fabric. This is seen in two examples shown (Fifth Maine Museum jacket and E. F. Barnes jacket). The distinct appearance of the twill lines in the Barnes example either represents heavy abrasion of the surface from “in service” wear or less napping in final finishing during its manufacture to reduce cost.

Also illustrated is the 3/1 (“three over one”) twill weave of the fabric used in the Bryan jacket which was discussed in the last slide. Other examples (e.g. Greer jacket) in the study have a 2/1 (“two over one”) weave. The twill pattern in such cases is not as distinct visually as the 2/2 “kersey” weave. Finally, non-twill, plain (termed “tabby”) woven fabric was also used. One of the examples in the comparative study, the Gettysburg NPS jacket was constructed from such cloth as was the Charles A. Milhouse jacket in the extended group. Plain weave material was also used in a late 1864 pair of RCB made trousers in the collection of the Smithsonian that belonged to Maryland artilleryman George Wilson whose jacket another one of the studied examples.

Comparison of weave patterns in English “Army Cloth” found in RCB jackets:

Domestic Woolen Goods for RCB Uniform Production

Woolen goods for uniform production were generally contracted by the QM Department directly from local mills although they also purchased lots from Richmond dry goods merchants.

At least seven mills in Virginia produced all wool or “wool on cotton warp” fabric for the RCB.

These included: Crenshaw Woolen Mills (burned May 1863), Kelly, Tackett & Ford, Manchester Cotton and Wool Manufacturing Co., Bonsack & Whitmore, Scottsville Manufacturing Co., Danville Manufacturing Co., and J. B. Pace

While several mills supplied significant amounts of all wool material early in the war (especially Crenshaw), most was “wool on cotton warp” fabric (jeans, satinette, cassimere, and plain weave).

Period records seldom indicate color for domestically produced material but mills probably did the dyeing themselves.

From existing examples most seems to have been “yarn dyed” wool “fill” on a natural or light brown cotton warp

In 1861 Crenshaw procured a cargo of logwood dye for its own use and sold it to other mills for their use

Whe re mentioned, “grey”, “cadet”, “drab”, as well as “blue” (for pants) are the colors most frequently seen.

Contracts with Crenshaw, KT&F and the Manchester Cotton and Wool Mfg. Co. were referenced in Captain Richard Waller’s 1863 report to Quartermaster A. C. Meyers (Source: Richard Waller to A. C. Meyers, Letter 24 April 1863, M410, RG 109 NARA). Following the fire which destroyed the Crenshaw works, the other six firms were listed in The Shipping Book ledger as delivering woolen goods to the RCB throughout the remainder of the war. In 1861 and 1862 some woolens also were procured from mills in the deep south, especially Georgia. By the end of 1863 apparently all domestic fabric used by the RCB was sourced on Virginia firms. The RCB also purchased fabric from wholesale dry goods merchants in Richmond such as Kent, Paine, & Co. and Ellett & Drewry throughout the war. For example, the RCB bought a lot of 2676 ¾ yards of gray “army cloth” from Kent, Paine & Co. on 17 December 1864.

In most cases the weave was not specified in The Shipping Book except for Bonsack which apparently only produced Jeans. Jeans, cassimere, satinette, and plain weave (“plains”) “wool on cotton warp” fabrics are listed in invoices from KT&F, Manchester, and Richmond dry goods companies and are found in surviving Richmond products. The majority of entries in The Shipping Book also do not indicate color although occasional references are to “grey” or “blue” material do occur. Invoices from KT&F and Manchester list “grey”, “cadet cassimere”, and “drab cassimere” among the entries for what the provided. It is unclear if “cadet” refers to a blue-gray hue or may only be a general term used for gray dyed material (either yarn or piece dyed). “Drab” probably implies undyed woolen yarn – cream or sheep’s gray – on natural or brown cotton warp to yield a dull light brown or yellowish shade. (Sources: The Shipping Book and records for the various business firms listed above in the Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms 1861 – 1865, RG 109 NARA).

Domestic Wool on Cotton Warp Fabric used for RD jackets

The five examples shown in the pictures below (some from outside the study) illustrate the diversity of “wool on cotton warp” fabrics produced by domestic mills and used in RCB production. The Royall jacket is made from a course satinette while the Bernard jacket appears to be of a plain weave although the quality of the existent pictures (its current location is not known) makes conclusive determination impossible. The fabric used in the Adler and Vrenderburg examples was jean weave which was probably the most normally used type and the Hollyday trousers are of either jeans or cassimere. All are likely “yarn dyed”, that is the woolen yarn used in the fill was dyed before weaving, or possibly “dyed in the wool”. None appear to be “piece dyed” as the warp in each is natural, undyed cotton. As is discussed earlier, the RCB is known to have procured raw wool along with cotton warps, supplying them directly to the mills. The spun yarn (or raw wool) was logwood or vegetable dyed at the mills. Crenshaw is known to have procured a large shipment of logwood dyestuff from the Blockade Runner Tropic Wind in 1861 and sold quantities of it to other producers in Virginia. The RCB also is known to have supplied logwood dyestuff to mills for use in fabric production. Differences in the shade when the dyes faded (e.g. Royall or Bernard jackets vs. Adler and Vrendenburg examples) possibly occurred because of different mordants, dye modifiers, or times in processing. Generally, the “as issued” color of the fabric would range from medium to dark gray (almost black).

Thomas Vredenburg jacket – jeans weave, gray dyed wool on natural cotton warp (now partially faded)

Henry Hollyday trousers – jeans or cassimere weave, gray dyed wool on natural cotton warp (now partially faded)

George S. Bernard jacket – plain weave, gray dyed wool on natural cotton warp (now faded)

Abraham Adler jacket – jeans weave, gray dyed wool on natural cotton warp (note unfaded area under epaulette)

John Blair Royall jacket – satinette weave, gray dyed wool on natural cotton warp (now faded)

Cotton “Osnaburg” used in Richmond Clothing Bureau Jackets

14 jackets in the study have linings made of a cotton fabric described in period documents as “osnaburg”

The lone exception, the Tolson jacket, also has such material in the “as issued” sleeve linings

“Osnaburg” fabric is heavy, unbleached or undyed, and is plain or “tabby” weave

Two slightly different versions of the fabric were found among the samples in the study

11 of the 15 jackets have tightly woven with fairly uniform gauge cotton yarn

3 are more loosely woven of yarn that has a somewhat uneven gauge

After the middle of 1863 nearly all of the “cotton goods” used at the RCB were from 3 mills located in Petersburg (Battersea, Etterick, and Matoaca).

Earlier in the war Eagle Cotton Mills in Georgia supplied some of the cotton fabric for RCB production

From these mills, 1,095,583 yards of cotton fabric were received in the last six months of 1863 and 776,789 yards in the six months following that.

While wool shortages limited expansion of domestic woolen fabric production ultimately encouraging large scale importation of English “woolen goods” through the Blockade, cotton fabric was, if not abundant, certainly plentiful enough that Government needs at the RCB were met with little difficulty. Diverse types of cotton fabric appear on RBC inventories including “shirting”, “sheeting” and “drill” but “osnaburg” is found regularly and was the material of choice for uniform linings. Osnaburg is the period name for a relatively heavy, undyed or unbleached material which was woven in a plain or “tabby” style.

Of the jackets in the study group all were likely originally lined both in the body and the sleeves using this type of fabric. Only the Tolson jacket currently is not, as has been previously discussed, although the entry in his diary and the presence of original osnaburg sleeve linings supports the fact that it did “as manufactured”. The material used in the jacket linings of the other 14 examples is generally very similar although two slightly different versions are noted. In eleven of the jackets, the material is made from uniform gauge yarn which is tightly woven to produce a smooth appearance. The other three display a more loosely woven character and the yarn is somewhat uneven in gauge yielding a surface appearance resembling modern linen. Such differences could represent different source mills, variation in quality in different “runs” of the product, or even different grades of material

While early in the war Georgia mills, and to some extent others in NC, provided cotton goods to for uniform production, by the mid war period Battersea, Etterick and Matoaca, three mills located in Petersburg, produced nearly all cotton fabric used at the RBC. The quantity of “cotton goods” contracted for and received was staggering. In just the period between 1 July 1863 and the end of that year, 1,095,538 yards of such material was received by the RCB with another 776,789 yards in the six months after that.

The pictures below illustrate the two slightly different types of “osnaburg” that were present in the study group. Three samples had more uneven yarns somewhat loosely woven (i.e. Fifth Maine Museum, John Blair Royall and Charles S. Tinges jackets) while the rest display the tightly woven type made from very uniform yarn (Joseph W. Brunson and George W. Wilson jackets are shown). While the resultant surface appearance was different the fabrics were otherwise nearly identical. As noted in the last slide, such differences could represent different sources, different production “runs”, or possibly different quality grades.

Fifth Maine Museum Jacket – loose weave, uneven yarn

Joseph W Brunson jacket – tight weave, more even yarn

John Blair Royall jacket – loose weave, uneven yarn

George W Wilson jacket - tight weave, more even yarn

Hand Stitching in RD Jackets

Most RCB made jackets were hand sewn by piece workers who worked at home and were typically relatives of active soldiers or ones who had died in the service.

Four types of hand stitching were commonly used:

“Running” or plain “over and under” stitching – typically used for interior (hidden) seams or top stitching

“Overcast”, “whip” or edge stitching – used to attach linings and join sleeve linings to body lining inside the jacket at the armscye

“Button hole” stitching – binding button holes and at the edges of the inside pocket opening

“Back” stitching –occasionally seen in interior (hidden) seams or in topstitching

The vast majority of RCB garments were sewn by hand. In the study group, even in cases where machine sewing is found, some amount of hand stitching still is seen. Unlike the Schuylkill Arsenal, after which it was modeled, when established (circa 1861) the RCB had no pre-existing workforce of pieceworkers in Richmond for garment assembly. Period documents and newspapers support the observation that most workers assembling the garments were women, often family members of men in Confederate service and, in many cases, were dependent upon the wages received from their work for living expenses. They received the “kits” (usually in multiples of as many as 12 at a time) from the Bureau which presumably included thread for their work. Most period women had some experience in sewing, perhaps having made garments for their families, and would have been familiar with some number of stitching techniques.

Four different stitching methods were identified in the study examples. The most common technique was the “running” or plain “over and under” stitch. This type was executed by simply advancing the stitches by passing the needle back and forth through the material at standard intervals. It was used in internal (hidden) seams joining different pattern pieces and in “top stitching” along the edges of the garment. The “running” stitch does not provide a “lock” to prevent seams from unraveling when the thread breaks. Many seams observed in the study jackets have begun to come apart due to this. Another technique found in the jackets that mitigates this problem is “back” stitching. This also was occasionally used for internal seams and, more rarely, for top stitching. This technique takes somewhat longer and uses more (expensive) thread which is probably why it is less frequently encountered.

The second most common stitching technique is “overcast”, “whip” or edge stitching. This was employed in closing the neck/collar opening, attaching sleeve linings and sometimes connecting facings to linings. Like the “running” stitch, “overcast” stitching does not provide “locking” to prevent unraveling when the thread breaks. This stitching method is very handy for “felling”, i.e. sewing down the edge where one-piece overlaps another. The final type is the “button hole” stitch, a specialized technique for binding button holes using a “crochet-like” stitch that prevents unraveling of a raw edge. By its nature this provides a “lock” that limits the problem. For this reason, perhaps, in nearly all the study jackets this stitch was also used to bind the edge of the inside pocket opening.

Hand stitching in the study jackets varied in quality, done quite competently in some and rather poorly in others showing hasty execution. Generally, however, the spacing on all examples is reasonably evenly spaced at between six to eight stitches per inch.

The telltale pattern seen on the reverse of top stitching done with the “back” stitch is clearly visible in this period image of Sergeant Thomas Crowder Owens wearing a RD type I jacket from Jensen’s 1989 article in MC&H. The “back” stitch is executed by advancing the stitches in line, bringing the needle from the underside (reverse) ahead of the last stitch, and returning through the point where the last stitch was completed. The “half back” stitch is essentially the same except that the return only is taken half way back to the end of the last stitch. This is also occasionally seen in RD jackets. The pattern created by both on the reverse side is of overlapping stitches somewhat misaligned with each other.

Machine Sewing in Richmond Jackets

Examples of machine sewing on RCB jackets are seen in the relatively small sample examined in this study

Use of this technology represents something of an anomaly in construction based upon the “typical” model of RCB operations

Hand stitching was then the “norm” for home workers.

They weren’t used in the pre war army at Schuylkill Arsenal due to doubts about the quality of their results

Sewing machine technology was known in Richmond and used in other CS Government operations

In 1860 seven separate firms were selling sewing machines

Union Sewing Machine Co. established a Richmond factory in 1860 to make them.

CS Ordnance Dept. bought new machines, spare parts, and contracted for repair services

No record of CS Quartermaster Dept. use although some of its vendors ( e.g. for cap bills) did.

Indirect evidence suggests the RCB may have utilized professional seamstresses, tailors and/or dry goods firms who might have used such devices to assemble garments.

1864 articles in Richmond papers indicate that “clothing makers” would have work certificates (needed to get clothing “kits “ for assembly) taken away and “transferred to soldiers’ families ”in need.”

As has been discussed in Part 1 of this presentation, two of the jackets in the study group are partially or almost completely sewn by machine and, at least, two in the extended group also exhibit machine stitching. Given the small sample size, such a high ratio of machine stitching represents an anomaly that refutes the commonly held belief that Richmond jackets were always completely hand stitched.

The first “lock stitch” sewing machine was patented in 1854 by Elias Howe and throughout the remainder of that decade their popularity rose. Seven separate firms selling them were listed in the 1860 Richmond City Business Directory: Groyer & Baker; Ladd, Webster & Co; Lester’s; Old Dominion; Singer’s; Wheeler & Wilson’s; and Willcox & Gibb’s. Not only was “Lester’s” selling sewing machines, it was also manufacturing them at a plant located in the city under the name Union Sewing Machine Co. Period references indicate that the wealthier Richmond households had and used them. For example, in Mary Chestnut's Civil War Diary, she complains that before a sewing bee organized by Varina Davis (Jefferson Davis’ wife) to make garments for the Confederacy, she (Chestnut) begged Varina to let the women bring their sewing machines because so many more garments could be made in the same time using the machines but Varina had refused and the ladies worked by hand.

Sewing machines were not used at the pre-war Schuylkill Arsenal, the model for RBC operations, due to concerns by the US Army Quartermaster Department over the quality of the results believing that “[h]and-sewn garments were considered to be more durable” (Source: Erna Risch, Quartermaster Support of the Army, A History of the Corps 1775–1939). A.C. Meyers, the first CS Quartermaster, was probably aware of this philosophy and there is no record that the Quartermaster department purchased or used sewing machines directly in its operations. Period newspaper references support the notion that most of the seamstresses who assembled the jackets worked at home, were poor, and relied on the money received for their living. Sewing machines were relatively expensive as were replacement parts (needles, spindles, etc.), thread, etc. and, as such, probably “out of reach” for the poor who represented most of the piece workers. Despite the QM Department’s apparent lack of use of machines itself, Government records indicate that the CS Ordnance Dept. purchased new machines (both “Lester’s” and Singer), replacement parts, and contracted for repair services from a different firm, the Union Manufacturing Co. during the war (Source: Records for the various business firms listed above in the Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms 1861 – 1865, NARA).

No documentation has been uncovered to explain who was using sewing machines in RD jacket assembly. It certainly could be that some of the soldier’s relatives who assembled uniforms owned and used them. It also may be that professional seamstresses, tailoring firms or even dry goods companies may have received “kits” from the RCB for assembly. Articles in the Richmond newspapers from 1863/1864 suggest that this may have been the case. An article in The Richmond Whig on 24 April 1864 states: “The Superintendent of the C. S. clothing Bureau has given notice that after the 10th of May all the clothing makers in this city must furnish a certificate … that they are the proper persons to whom the work should be given; otherwise their numbers will be taken away and transferred to soldiers' families” (Italics the author’s). It is significant that the degree of machine use vs. hand work is different on each jacket studied suggesting different workers were involved. Unfortunately, the answer to who worked on these jackets may never be known.

The pictures below show detailed views of the machine sewing found on two of the examples in the study group. On the Bryan jacket, the long internal seams in the outer body and top stitching along the edges was executed by machine. Interestingly, the body lining was done completely by hand stitching. Also notable is that the top stitching was done with different color thread for the “top” (visible from the outside) than the “bottom” (visible from the inside). The outside top stitching is now a brown color but was originally logwood or vegetable dyed and has now faded. The inside is undyed or “whited brown” thread. All the long interior seams are in the same “whited” thread possibly suggesting use of less expensive thread where it would not be seen.

The Brunson jacket was almost completely machine sewn. Only the stitching at the arm lining where it was attached to the body lining and the cuff, the top stitching on the cuff, attachment of the belt loops to the body shell, and button holes were done by hand. All thread used for the machine sewing was logwood or vegetable dyed including the long interior seams.

Thread

Both linen and cotton thread appears to have been used in production at the RCB

Domestic suppliers provided thread and large quantities were brought through the Blockade from England

The thread used was either natural colored (referred to as “whited brown”) or dyed with logwood or vegetable materials that faded to medium brown with exposure to light

Common thread used in hand sewing appears to be 2 ply, “S” (right hand) twist , and relatively heavy

From invoices for materials purchased by the RCB as well as records of both domestic and English imports found in The Shipping Book ledger, large amounts of linen and cotton thread were received by the Richmond operation. Numerous vendor invoices document procurement of large lots of thread in 1861 and 1862 from Richmond firms like Ellett & Drewry - black flax and black spool (cotton) thread, and Kent Paine & Co. – dark brown, whited brown flax thread and white spool thread (Source: Records for these business firms in the Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms 1861 – 1865, NARA). Numerous entries for thread shipments received by the RCB are noted in The Shipping Book. For example, on 5 August 1864, 1440 pounds of English “flax thread” were received in one shipment of English goods and the next day another 3494 pounds of (cotton) “spool thread” as part of another.

Based upon examples in the study both logwood or vegetable dyed thread and “whited brown” thread were used in RD jacket construction, probably supplied as part of the “kit” received by the assembly pieceworker. Logwood dyes, as discussed earlier, fade brown depending upon the mordant used and processing. It has been well documented that Federal contractors also used logwood dyed thread which faded to a medium to light brown hue of the thread observed on Union garments. Certain vegetable-based dyes used to substitute for logwood also turned a light brown with prolonged exposure to light.

Based upon detailed examination of the thread used in the studied jackets, the common thread used for hand sewing was relatively heavy 2 ply, “S” twist thread. The ply indicates the number of strands twisted together to make up final thread. The direction of twist, “S,” means that the final twist is in a “right hand” direction. Left hand twist thread is referred to as “Z” twist. Based strictly upon observation, the weight of the thread appears to be 20/2 or, possibly, 30/2 using today’s terminology. The first number is a measure of weight and relates to the number of yards of thread per pound. The second number is the ply. 20/2 thread is 2-ply and has 3000 yards to the pound while 30/2 is also 2-ply but has 4500 yards per pound. Period documents indicate pounds of thread received but do not specify the corresponding lengths. Close examination of machine sewed thread seems to indicate it was somewhat lighter in weight suggesting other sources for this material. No specific references to sewing machine specific thread were found in period documents, however.

The pictures below illustrate characteristics of the thread used on jackets from the study. The pictures of stitching on the Fifth Maine Museum example show the color transformation of the logwood/vegetable dyed thread. Unexposed areas inside this jacket display the original coloration of the thread when first used, a dark gray-brown. In areas on the reverse that have been exposed to light (i.e. top stitching along the bottom of the jacket and buttonholes) the thread color has changed to a medium brown. The closeup of the loose stitching from inside the cuff of the Greer jacket illustrates the relative thickness of the thread in comparison to the thumb in the photograph and the “S” twist in the strands in the thread itself.

Additional pictures seen below show the thread used in other study jackets. They display the progression of color change from brown-gray usually observed today in stitching seen inside the garments to a light brown on exterior parts consistently exposed to light.

A detail of the stitching on the Bryan jacket shows both hand stitching and machine stitching in closeup. The relative thickness of the thread used with the machine is noted, as is the “whited” color of what was used on the “bobbin” side (back) of the top stitching found on that jacket.

John J Haines jacket

George W. Wilson jacket

George Pettigrew Bryan jacket – note hand sewing at top, and machine sewing at bottom

William Pilcher jacket

Buttons

Buttons for RCB production came from domestic sources and through the Blockade.

Period RCB records show “military” and/or metal buttons as well as bone, tin, and agate

Large quantities of bone buttons in pant and shirt sizes, were procured for RCB use from the Union Manufacturing Co. and came from other sources

In early August 1864 the RCB received large shipments of English “military” coat buttons, metal pants buttons and metal shirt buttons brought through the Blockade to Wilmington

Between early 1863 and the end of 1864 the Richmond Clothing Bureau contracted with the firm of John and George Gibson, for wooden buttons

In all, the Gibson Brothers fulfilled contracts for a total of 12.4 million buttons in three sizes (coat, pants, and shirt)

These were used on RCB made clothing and on shelter halves made by the Quartermaster Department in Richmond

Numerous period photographs show soldiers wearing Richmond made clothing with Gibson buttons

In the field soldiers often substituted privately obtained buttons (particularly state buttons) for those on the jackets as issued

Procurement of buttons soldier’s garments appears to have been a challenge for the RCB. They utilized buttons from many diverse sources both domestic and imported through the Blockade. In Richmond alone, domestic producers such as E.M. Lewis & Co., S.A. Meyers, and W. Wildt & Son along with other firms produced “military” buttons based upon existent examples (source: Alphaeus H. Albert, Buttons of the Confederacy, 1963). “Military” buttons were also received in huge quantities as part of shipments from foreign sources throughout the war. For example, on 6 August 1864 The Shipping Book records receipt of 4000 gross “military” buttons from England. Several of the jackets in the extended group have buttons backmarked “S Issacs, Campbell & Co.” received in such shipments. Some “military” buttons used may also have been “gleaned” from captured Federal clothing or through battlefield salvage. The Federal “Eagle” buttons on the Greer and Redwood jackets could be original to those garments not later replacements.

Common button types, such as pant and shirt buttons used for RCB garment production, were also procured both domestically and by importation. The RCB contracted for large quantities of bone buttons from the Union Manufacturing Co. (same company who provided sewing machines and parts for the Ordinance Dept.) and purchased sizable lots of buttons (agate. bone, etc.) from Richmond wholesale Dry Goods firms like Ellett & Drewry. On 7 August 1864 The Shipping Book records receipt of 1080 gross metal pants buttons and 250 gross metal shirt buttons that had come through the Blockade into Wilmington (the day after they received the “military” button shipment described above) “Japanned” (black painted) stippled buttons seen on some RCB clothing likely came from such shipments.

Beyond these sources, the Clothing Bureau contracted with a Richmond carpentry company, John and George Gibson, to provide a truly phenomenal number of wooden buttons in three separate sizes (coat, pant, and shirt). Between early 1863 and early 1865 they executed three separate contracts for an aggregate of 12.4 million such buttons, of which 3.9 million alone were the coat size for use on jackets and, it appears, “Depot” produced shelter halves (source: Jim Schruefer, “John & George Gibson: Wooden Buttons for the Richmond Depot”, essay first published on www.blueandgraymarching.com). Three of the coats in the study group have such buttons as well as one in the extended group. Their presence is almost diagnostic of RBC manufacture.

In spite of the large numbers of buttons used on issued jackets or perhaps because of the use of such “non-military types“ as the Gibson wooden buttons, soldiers in the field frequently substituted buttons they obtained themselves for the “as issued” type, at least on their jackets. Many were buttons emblematic of the State from which they came. This is observed in the study group where, of the seven which definitely have replacement buttons, six have State emblems (3 MD, 2 VA, and one NC) while the other (Tolson) has US staff buttons.

The pictures below show examples of the types of wooden buttons made by the Gibson brothers as well as the types of products made by the RCB that used them. The Hollyday drawers and shirt, made by the RCB and issued early in 1865, have respectively the pant size and shirt size. In addition, the coat size seen on the Fifth Maine Museum and the Brunson examples from the study, are found on the Alfred May CS shelter half made in Richmond by James Butler & Co. for the “Depot”. Under contracts for these, the Gibson firm delivered nearly 4.3 million of the pant and shirt sizes to the RCB between October 1862 and January 1865 (sources: Chris Schneider, “Fly Tents and Shelter Halves: Confederate Tent Production in Richmond”, essay on https://www.libertyrifles.org/research/uniforms-equipment/confederate-tents, (2017) and Jim Schruefer, “John & George Gibson: Wooden Buttons for the Richmond Depot”, ibid).

Period pictures of soldiers from different units associated with Army of Northern Virginia illustrate the use of John and George Gibson’s products on Richmond type II jackets. The troops in the photographs are from North Carolina, Maryland and Virginia suggesting these were received through CS Quartermaster issue. John Gray’s picture is not a studio photograph but was taken after his capture. His jacket probably illustrates use in active service based upon the missing button. It likely was received earlier in 1864 but still appears to be in excellent condition.

By the middle of 1863, Gibson wooden buttons were common on RCB products. Closeups from this famous Alexander Gardner photograph taken of what are believed to be dead Georgia soldiers from fighting on 2 July 1863 at the Rose Farm in Gettysburg clearly show use on Richmond jackets issued to them in the first half of 1863.

This picture is of a dead Confederate soldier in the trenches at Ft. Mahone after it’s capture on 2 April 1865. The continued use of Gibson buttons on RCB garments late into the war is illustrated in the closeup photographs which show pant size buttons both on his trousers and drawers while one of the shirt size buttons is seen on the trouser fly. Gibson contract shipments were being received at the RCB as late as 21 January 1865, a little over two months before the death of this soldier. The shirt and drawers issued to Henry Hollyday of the 2nd Maryland Infantry in March 1865 also were made by the RCB and display both types.

Buttonholes

The quality of the buttonholes on Richmond jackets varies in the same way as the other handwork in the garments studied. Early in the 19th century, professional tailoring establishments began to employ specialists who concentrated specific aspects of making garments such as those termed “finishers” who only concentrated on doing buttonholes and other tasks in the final stages of garment fabrication. By the middle of the century, in larger firms that employed the “sweat” or “slophouse” system which decentralized the production even further, specialists were dedicated to unique tasks and “buttonholers”, whose only task was making buttonholes, were employed. Generally, wives and mothers who made clothing for family members learned to do buttonholes along with the other skills required for their work. The buttonholes on RCB products appear to not have been done by specialists but are the work of the individuals who assembled the jackets most of whom were likely prewar homemakers, and reflect their distinct experience levels as well as the rushed nature of the assembly process itself. Some were quite well done while in other cases they were more crudely, if still competently, executed.

The pictures below are illustrative of the range of workmanship in buttonholes on Type II examples from the study. The Fifth Maine Museum jacket buttonholes were quite competently executed as are those on the Royall jacket. The buttonholes on the Haines on Greer examples represent those somewhat more crudely worked.

Buttonholes on type II examples:

John J Haines jacket

George HT Greer jacket

John Blair Royall jacket

Fifth Maine Museum jacket

Below are photographs from type III examples and like the last slide display the range of quality in workmanship encountered among the studied jackets. The fine quality of those on the Tolson jacket represent among the best found in the studied jackets while the others demonstrate the typical range in quality observed.

Buttonholes on type III examples:

George W Wilson jacket

Henry Redwood jacket

Edwin F Barnes jacket

Thomas H Tolson jacket

Variations in Construction

The jackets studied were assembled with a similar strategy and generally similar construction techniques

While the major source for the most construction variations was “seamstress choice”, some may provide clues to the RCB manufacturing process.

Different fabrics used in the “kits” may account for some differences

Efficiently using “scarce” woolen fabrics caused “piecing” parts through use of scraps

“Kit” pieces may have been cut so pieceworkers could “adjust” assembly (e.g. facings & linings)

Deficiencies in the “kits” may have caused observed variations

Bureau inspectors focused more on “functional” aspects of garments than “technical” details

It is likely some pieceworkers were capable of making adjustments to facilitate assembly of the jackets as was required

Certain areas that consistently exhibit variations in construction that emphasize such points are:

Assembly of the lapel facing to the body lining

Construction of the collar and execution of the seam between the inner collar and the body lining.

Throughout this presentation variations in jacket construction have been highlighted. These variations or “anomalies” often represent the fact that multiple individuals assembled them who used different modes of construction, that is, “seamstress choice” techniques. However, the philosophy of how the jackets were intended to be fit together as embodied in the pattern pieces resulted in similar assembly strategies with generally similar construction techniques. Some variations do, it is believed, provide insight into the interactions between the RCB’s production process and the pieceworkers which, in turn, leads to a better understanding of the context in which the clothing was produced.

One example is that the diverse fabric types used influenced the techniques for working with them. Loosely woven fabrics like jeans or osnaburg have the tendency to unravel along cut or “raw” edges. Tightly woven ones like kersey or broadcloth tend to hold a raw edge without unraveling. “Felling” is the process of securing a cut edge to keep it from unraveling when worn. Loosely woven fabrics require either turning the edge under or overlapping it so that the raw edge is not exposed when felled. Material that holds a raw edge can simply be sewed down without being turned under. Experienced assembly workers would possibly have adapted the way they made seams depending upon what was supplied in the “kit” they received (e.g. wool kersey vs wool on cotton jeans cloth).

The difficulties in acquiring uniform fabric and its cost resulted in efficient use of available supplies. It was common in period production to “piece out” garments by sewing scraps together to utilize stock. Several of the jackets in the study display this as do products of many other CS and US (e.g. SA) uniform producers. It is not known who did “piecing”, employees at the RCB or the seamstresses who assembled the garments. The later would seem most likely because there is also some indication that pieceworkers regularly received “kit” parts cut to allow for adjustment of the fit between mating parts as they assembled the jackets. As experienced clothing makers from their work at home, most pieceworkers probably could adjust what they received for better assembly.

Given the thousands of “kits” prepared (estimate 1500 – 2000 daily) at the RCB, the possibility of miscounting pieces or dealing with shortages in items like buttons probably resulted in deficiencies in individual “kits”. Like at Schuylkill Arsenal, when they received the “kits”, assembly pieceworkers were charged for the value of the materials pending return of the finished garment and acceptance of their work. For seamstresses making garments, deficiencies may have resulted in modifications to the way they made up the “kits” so they could finish and be paid for them. The Greer jacket with only six buttons or the frequency of 8 button Type III jackets could be represent such a phenomenon. Even single piece epaulettes found on the Ramsey and other late Type II jackets could be a change in pattern prompted because seamstresses had learned to “adjust kits” which had only two rather than four epaulette pieces as received. That such “anomalies” were apparently passed by the inspectors at the RCB perhaps indicates their criteria was more “functionally focused” on sturdiness and wear-ability than on the “technically focused” adherence to a “sealed standard” of how the jacket was supposed to be made.

Two areas will be discussed where differences in construction were observed will be investigated to illustrate some of the points made above. It is noted that attempting to derive rationale for the differences is, at best, informed speculation based upon research and deductive analysis. Other explanations may certainly be valid.

The first area where construction variations are considered significant is the inside lapel facings on RD jackets and the way they were attached to the front lining panels is an area of pattern and construction that showed significant variation in the fifteen studied examples. The variations illustrate several of the points discussed in the last slide. The picture of the right lapel facing inside the Fifth Maine Museum jacket shown in this slide basically illustrates the typical facing pattern and construction approach found in these jackets. The facing is normally roughly the same width top to bottom with the seam between the facing and the front body lining panel straight or slightly curved to match the line of the front. The facing is attached to the lining by a “Plain” (or superimposed) seam where the “right” sides of the facing and lining are laid together and stitched with either “running” or “back” stitches along the edge where they join. The seam allowances are then pressed back toward the lining. The Fifth Maine Museum facing is an excellent example of where “piecing” has been used to sew together small material “scraps” to make a finished pattern element. Three jackets in the study group have such “piecing” in the lapel facings.

Below are pictures of four other examples that illustrate the “typical” shape of the lapel facings and how they are usually attached to the body lining by a “plain” seam that has been pressed back in the direction of the lining.

John J Haines Jacket

John Blair Royall Jacket

Gettysburg NPS Jacket

Henry Redwood Jacket

Two significant variations observed in the study group are illustrated by the pictures below observed are shown in this slide: oddly shaped lapel facings and a change in the way the facings are attached to the body lining.

The Brunson and Barnes jacket facings are much wider at the top (neck) end and narrow toward the hem (bottom) end. This narrowing is so extreme in the case of the Brunson example that the last two button holes at the bottom lap over into the lining. Most likely this was another example where the “cutters” at the RCB made maximum use of oddly shaped scraps left over after cutting out pieces for a run of jackets. In both jackets, the facings were attached to the front panel of the body lining with a “plain” seam in the usual fashion. This is significant because to accomplish this, the lining panel needed to be shaped differently from normal (last slide) to be connected to the facing using that method. This, in turn, suggests either that these linings were cut at the RCB to match the facings for these specific jackets or the body lining panels were left long enough that they could be adjusted during assembly.

The other two jackets (Bryan and the Wilson) illustrate a second variation observed. Both have more or less “normally” shaped facings but the method of attachment is an “lap” seam where the lining passes under the facing and the facing edge is “felled” down using “overcast” stitching. The lining in these cases extends to the front edge of the jacket also acting as an interfacing. This construction technique is enabled because of the use of EAC in these jackets which is a tightly woven fabric that holds its cut edge and can be directly “felled” without unraveling issues.

It is noted that if front lining panels were always shaped to extend to the jacket edge by “cutters” at the RCB, seamstresses who assembled the jacket could utilize them either trimming back the lining for the seam to match the facing shape or accommodating the overlap of the lining by the facing, eliminating the requirement for a separate interfacing. While speculative, this would have allowed “standard” front lining panels to be used in the kits to allow a reasonably competent period worker to easily use either method when assembling the jacket.

Oddly shaped facings joined by “typical” seam to lining:

J W Brunson Jacket

E F Barnes Jacket

“Typical” shape but facing overlaps lining (overcast)

George Pettigrew Bryan Jacket

George W Wilson Jacket

The following pictures show perhaps the most fascinating example of lapel construction variances is William Pilcher jacket where both types of seaming were used in the same example. The way the facing to lining was handled in this example (shown in the pictures in this slide) seems confirm the above speculation on how the RCB “cutters” made front lining pieces in jacket “kits” distributed to pieceworkers.

On this jacket, the left side (with buttonholes) was executed as a “plain” seam using a “running” stitch where the seam allowances were pressed back as has been described. On the right side (with buttons) the lining extends underneath the facing to the front edge. The facing was attached to the lining in a “lap” seam with “overcast” stitching. It is not believed that the difference is a mistake by the seamstress (“goof”) nor the work of two different workers. This is instead a perfectly reasonable construction technique to provide interfacing to strengthen the side with buttons while eliminating the underlay where the buttonholes are located. As with the examples in the last slide, use of the “lap” joint with simple “raw” edge “felling” is enabled by the tightly woven kersey weave EAC.

It is believed unlikely that the front lining panels provided in the “kits” were cut differently by the RCB. Such a process would imply extra work to create two different lining panels, one left and one right. It would also complicate the preparation of the “kits” themselves requiring RCB staff to properly sort different pieces in constituting them. However, if both pieces were cut to be long (to reach the edge of the front), then the seamstress could adjust the shape of the pieces as required, cutting them short to make a “plain” seam, leaving them long to pass under the facing as an interfacing, or as in this case making one each way. While clearly only circumstantial evidence, this strongly supports the theory that the front lining panels were cut to enable adjustments in assembly.

William Pilcher Jacket – Both types of joinery in the same jacket:

A second area where construction variations noted seem significant is in the collar construction and how the neck seam was done where the body lining and inner collar meet. Two significantly different approaches were found as well as relatively minor “seamstress choice” variations on those themes. The drawings below illustrate diagrammatically the differences. In Method 1, which was the more “typical” technique, the outer and inner collar pieces were sewn together and turned inside out, basically assembling the collar first. The assembled collar was sewn to the neck of the outer body shell before attachment of the body lining/facing assembly. Once the lining was sewn on and turned, the inner collar at the inside neck opening was closed using one of three different “felling” techniques to attach the lining in an “lap” seam. In 1A the facing/lining was turned under and sewed down over the inner collar. Variation 1B basically is the reverse, the inner collar is turned up and overlaps the facing/lining. Finally, 1C which is only observed in later EAC jackets, where the inner collar simply has the “raw” edged “felled” down to the facing/lining to complete the “lap” seam. Variations 1A, B, and C clearly are different “seamstress choice” approaches to a common assembly operation which reflect personal taste and the nature of the materials being used.

Two of the jackets in the group, the John J. Haines and Joseph W. Brunson examples, exhibit an unusual approach depicted in the slide as Method 2. Given that these jackets were made perhaps as much as a year and a half apart and one was completely hand sewn while the other nearly all by machine, the similarity in their construction is noteworthy. The figure provides a schematic representation of what was done but the actual process was somewhat more involved. To accomplish this, the outer collar piece was sewn to the outer body shell as a “plain” seam and the seam allowances pressed flat. Before being joined to the outer collar, the seam where the inner collar joins the facing /lining was sewn separately also as a “plain” seam and those seam allowances pressed flat. The body lining, with the lapel facings and inner collar attached, was then aligned with the assembled outer body (without sleeves) and outer collar, such that the finished (right) sides were together. The outer shell was sewn to the lining assembly around the entire periphery, that is, down the front on each lapel, along the bottom hem and around the outer (top) edge of the collar. The jacket was then turned right side out through an arm hole and topstitched around the periphery. A secondary line of running stitches was added to the collar above the neck seam that tied the collar pieces together. The picture looking the inside of the Haines jacket collar where the stitching has broken shows how the collar was done. While sounding complicated, this method probably involves about the same amount of work, results in less bulk at the neck seam, and, for the machine sewn Brunson jacket, allowed more effective use of the machine in completion of the garment.

One other jacket, the Bryan jacket, which like the Brunson was machine sewn, is sort of a hybrid where the facings are attached this way but the body lining at the neck like on the front panels, extends underneath the inner collar so the raw edge “felled” directly to the lining.

Different methods used in RD jackets collar construction and neck closure

Below are closeups of four jackets from the study that illustrate examples of Method 1 type A & B collar closures. The Greer and Knight examples use the type A “lap” seam where the lining overlaps the collar and is turned down before being “overcast” down. The Royall and Gettysburg NPS jackets illustrate the type B variation which is essentially the reverse of the type A. The inner collar overlaps the lining and is turned under (up) before being sewed down.

Method 1 type A - Collar closure details:

George H T Greer jacket 1 A

Lewis K Knight jacket 1 A

Method 1 type B - Collar closure details:

John Blair Royall jacket 1 B

Gettysburg NPS jacket 1 B

TTwo more examples of 1B closures and two type 1C closures are shown below. Two later jackets, Pilcher and Barnes, have their EAC inner collars turned up before being sewn to the facing/lining at the neck (type B). The Fifth Maine Museum and Wilson examples illustrate the type C with their inner collar “felled” along the raw edge. Because the Tolson jacket has been modified to remove the body lining, the inner collar area was obviously disrupted. However, it also appears that this also was originally a 1C type closure. Based upon somewhat limited photographic evidence, other late jackets in the extended group also show the type C closure suggesting that piece workers used the tight weave characteristics of EAC in “felling”.

Method 1 type B - Collar closure details:

William Pilcher jacket 1 B

Edwin F Barnes jacket 1 B

Method 1 type C - Collar closure details:

Fifth Maine Museum jacket 1 C

George W Wilson jacket 1 C

The following pictures show the method 2 closure approach seen on several jackets, especially the John J. Haines jacket and the Joseph W. Brunson example. The inner collar closure on these are sewn using a “plain” seam with the seam allowances pressed apart. The closeup detail of the inside of the Haines collar shows this and the stitching (machine) is clearly visible between the collar and facing can be seen in the Brunson picture.

The Bryan jacket appears to be something of a hybrid in which the facing has been sewed to the collar by a “plain” seam but the neck of the body lining like the front panel of the body lining extend under the collar and facing and is “felled” down.

Method 2 Collar closure detail – Inner collar sewed to facing /lining directly before assembly to outside collar:

John J Haines jacket Method 2

Detail showing inside of Haines jacket collar

Joseph W Brunson jacket Method 2

George Pettigrew Bryan jacket Method 2 (facing only) - Lining 1 C

Final Thoughts on RCB Production Operation

The RCB’s operations appear anachronistic compared to today’s “mass production” garment industry

RCB’s production model operated like a “cottage industry” that relied upon extensive hand operations

“Cutters” cut out each garment individually

Piece workers assembled them one at a time “at home” with simple tools and “low volume” methods

The high cost of “scarce” materials dominated the low cost of “abundant” labor

Materials (fabrics, notions) used were neither standardized nor readily available, they adapted the operations to use what they had at any time

Technology had marginal impact

The sewing machine while known was costly and not available in most homes but some degree of application is noted

Table “knives” and fabric spreading machines were not available in the period

Workers had a range of skills

“Cutters” probably could make and modify patterns

Many piece workers were likely competent enough to make adjustments and change assembly methods as required

“Kits” parts were possibly cut so piece workers could fit or adjust pieces to “make them work”

Inspection criteria for the finished work appears to have been more “functional” than “technical”

Bottom Line: Absolute consistency in the output garments was neither easily obtainable nor the primary objective

The 15 jackets studied were each different in some way but share characteristics that imply a common source of manufacture

While practical field clothing, they do achieve a level of “military style” by the design intent of the common pattern

Although displaying “seamstress choice” variations and “goofs” they still embody a common implementation strategy

Each is competently and “economically” made

In the 1860’s the readymade clothing industry was in it’s infancy. By the time the war started, the tailor’s trade was shifting from the “generalist” tailor who performed all tasks in garment production toward a more decentralized system, known as the “sweat” system that utilized piece workers organized by agents or “sweaters” to whom work was subcontracted by wholesalers or contractors. Some workers worked from home but, in most cases, were in dedicated rooms where multiple individuals were employed, often using sewing machines. The system encouraged division of labor, favoring specialists concentrating on limited tasks such as “Cutters”, Pressers”, and “Buttonholers.” Much clothing made for Federal troops was made by contractors employing such operations. (Source: Patrick Brown, “For Fatigue Purposes-The Army Sack Coat of 1858 – 1872”). The Schuylkill Arsenal which produced Union uniform clothing for over half a Century before the war, differed in that it centrally managed pattern creation/cutting activities and rigorously inspected finished products but relied on thousands of less specialized, more “generalist” home workers for all tasks in garment construction.

Viewing the RCB from the context of today’s garment industry seems anachronistic in many ways. Since the RCB initially modeled its operations around the Schuylkill Arsenal (SA) process, many parallels exist in the operations of each facility. Fundamentally, the use of large numbers of “generalist” home-based workers to construct the garments and the dependence on mostly manual methods for cutting and assembling them created a “cottage industry” production model as opposed to “assembly lines” or “sweat shops”. The “high” cost of materials and “low” cost of labor combined with the relatively high skill level of the seamstresses encouraged maximum use of scrap material. The workers would adjust how they constructed garments to allow for differences in the “kits” that were provided to them. In fact, the pieces in the “kits” that were provided may have even been cut to facilitate flexibility in assembly. Assembly variations were also precipitated by non-standardization of fabrics (different widths, weaves, fiber composition, etc.) and notions (buttons, thread, etc.) for garment manufacture. Assembly in the home environment relied on simple tools. Despite the use of sewing machines in some of the jackets in the study, there was no wide scale use of such technology. Mechanical advances such as table knives and fabric spreaders were not being used at the RCB because they were not available at this time. Instead, each garment was cut out by hand. It is not known whether the RCB followed the SA practice using “sealed samples” made by the Clothing Bureau itself to guide assembly workers and inspectors. Given the observed “anomalies,” however, their inspectors were clearly more concerned about the sturdiness and wear-ability of the final product (functional criteria) than on the precision or consistency measured against some assembly standard (technical criteria). Overall, 20th Century levels of consistency were neither obtainable nor the main objective.

The fact is that the entire universe of existing original RCB jackets represents less 0.02% of the total produced by its operation so the conclusions must be tempered by the very limited sample size available. What has been learned in this study, however, reinforces the elements identify them as the product of a single operation while demonstrating how the RCB managed production of hundreds of thousands of largely serviceable uniforms in the face of supply chain difficulties with little technological support. While the jackets each display minor variations, they represent good, functional clothing for field use, competently and “economically” made, using a common construction strategy.