Notes on Commissary Cooking and Equipment: 1861-1865

By The LR Research Committee

Many have written about Civil War rations and how individual soldiers prepared their meals. But most soldiers’ meals did not come from their haversacks. They came from the kettles and ladles of their regimental cooks.

When camp equipment lagged behind, soldiers were issued marching rations and fended for themselves. But soldiers did not spend most of their service campaigning. They spent much of their time stationary, enjoying the meager benefits of camp life. In these camps soldiers looked three times a day to men tasked with turning army provisions into meals. Reflecting on his service as a commissary officer, Captain S.S. Patterson wrote:

In a fixed camp or winter quarters it is a great advantage to have a regular cook and cookhouse - for each company. It saves time for the men, and makes them devote more attention to cleanliness and drill. It saves rations, is far more healthful, comfortable, and (properly conducted) satisfactory.(1)

Civil War armies recognized the importance of effective subsistence administration and worked tirelessly to refine the craft. The last step before this food reached soldiers were unit commissaries and cooks. These commissaries employed commons tools and techniques to complete the task.

This study examines the process of food preparation and distribution through photographs, sketches and paintings. The photographs have been grouped as Cooking Methods and Equipment and Tools.

Cooking Methods

Cook Fires

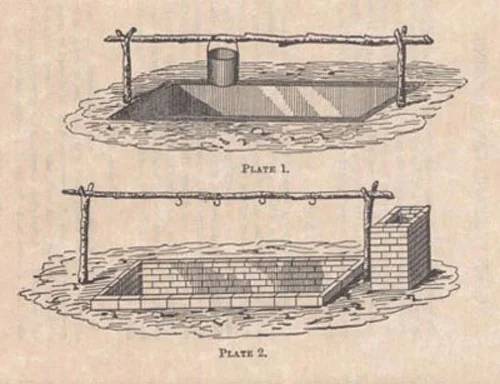

In 1862 the U.S. Government Printing Office published for distribution to the troops, “Camp Fires and Camp Cooking; or Culinary Hints for the Soldier;” by Captain James M. Sanderson. His guide provided the following diagram:(2)

Sanderson's diagram

Comparing this image to photographs and sketches of soldiers in the field, many agreed that Sanderson was onto something.

In 1861 at Fortress Monroe, Duryee’s Zouaves were ahead of the curve. They imitated Sanderson’s method almost exactly. These soldiers even had iron equipment made for the task.

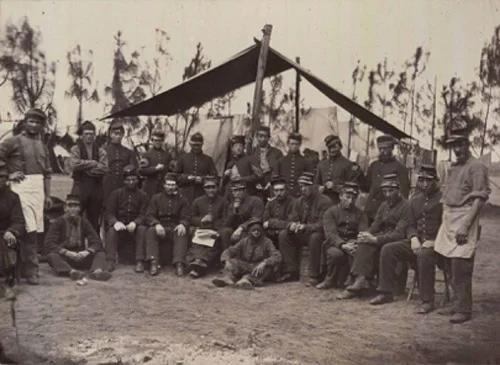

Fortress Monroe, Col. Duryee’s Zouaves(3)

Sanderson likes this method but warns soldiers that it,

... is neither the best nor most economical mode, as it consumes much fuel, wastes much of the heat, and causes great inconvenience to the cook. An improvement can be effected by casing the sides of the trench with brick, adding a little chimney at one end, and, in place of forked sticks, using iron uprights and cross bar, to which half a dozen hooks for hanging kettles are attached.

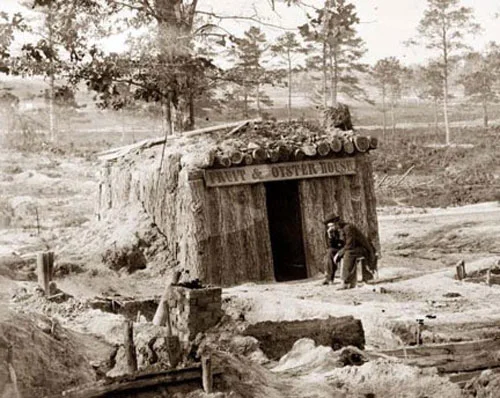

This 1863 photograph by Timothy O’Sullivan shows the possible remnants of Sanderson's method. Note the small chimney and pit in the center left of this photograph.

Petersburg, Va. Sutler's bomb-proof “Fruit and Oyster House"(4)

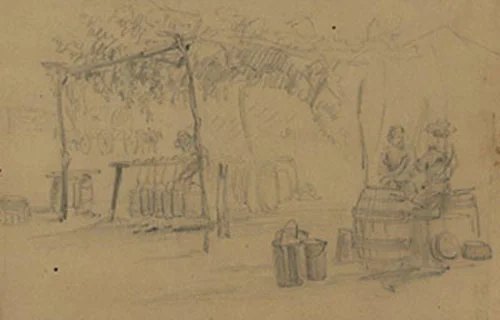

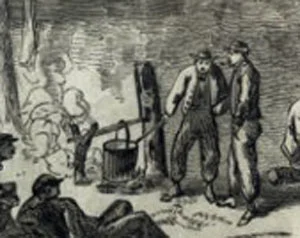

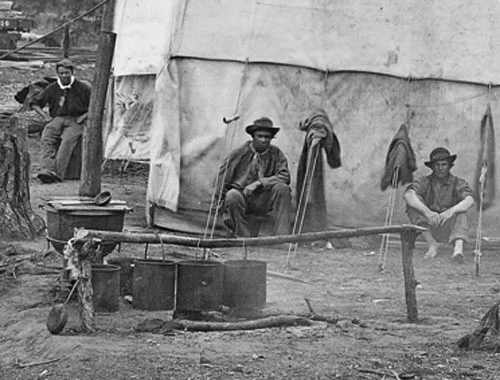

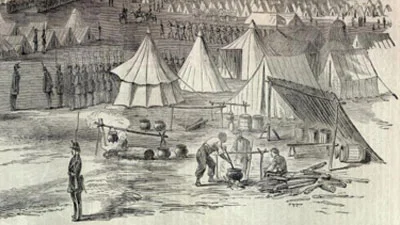

However, most cooks did not follow Sanderson’s method exactly, but used a similar style. The most common cook fire seen was made using forked sticks and a crossbar spanning the fire. Sanderson may have been disappointed by their inefficiency, but most field cooks did not bother with a pit or chimney. Pots often hung by their handles or ‘S’ shaped hooks.

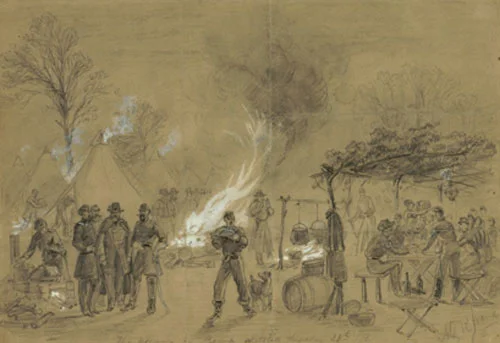

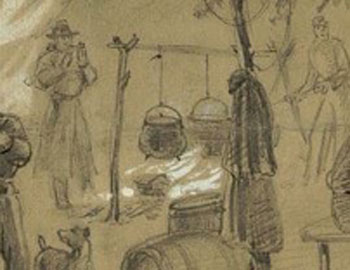

Capt. Ballerman’s Kitchen: Tasting the Soup(5)

Detail

Long “S” hooks were used by these cooks to hang the pots closer to the fire:

Detail from “Harrison’s Landing” by Alfred Waud(6)

The remnants of a cook fire and a coffee pot are depicted in this August 1863 sketch by Edwin Forbes. Various kettles, wash tubs and a pair of frying pans are also shown. Likely one of the chests may have carried these items.

“Our kitchen near Beverly Ford” by Edwin Forbes(7)

An axe, frying pan and makeshift table surround this cook fire:

Detail from "The Camp of the Seventh Regiment near Frederick, Maryland" by Sanford Robinson Gifford (1863)(8)

One of the more creative variations – using a fence post on one end:

“Ellsworth’s Soldiers in Camp” from Harper’s Weekly: June 8, 1861(9)

Detail

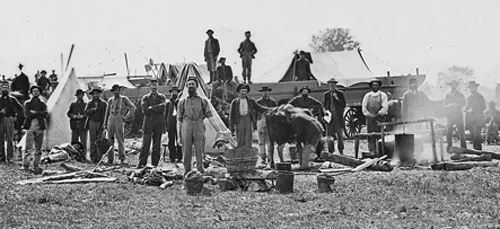

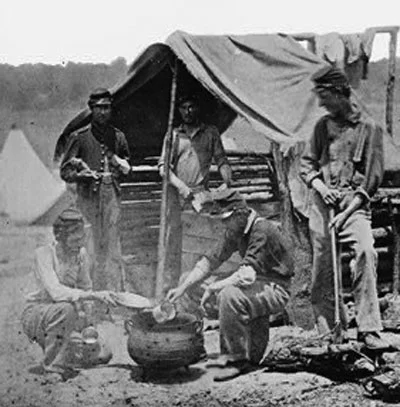

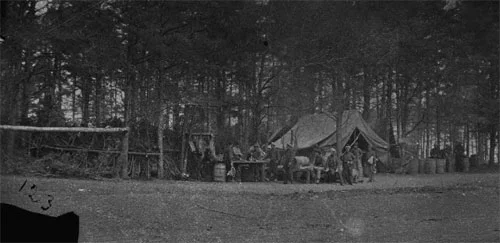

Another view of a camp kitchen typified by hand tools, camp chairs, mess kettles, a wooden bucket and cloth buckets. The cooks are utilizing two crossbars for their kettles. A soldier milks a cow near the center and pontoons can be seen in the background.

Detail from “Cooks’ Quarters”(10)

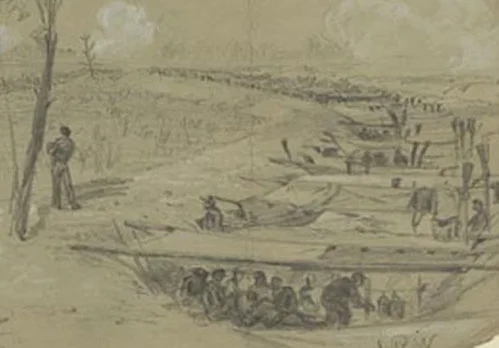

Even the trenches were a place for this familiar cooking method:

Detail from “Bivouacked in the rifle pits 5th corps” by Alfred Waud (July 1864)(11)

City Point, Va. African American army cook at work(12)

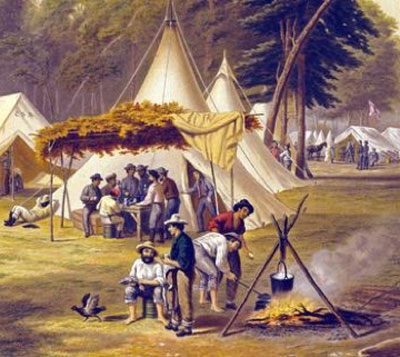

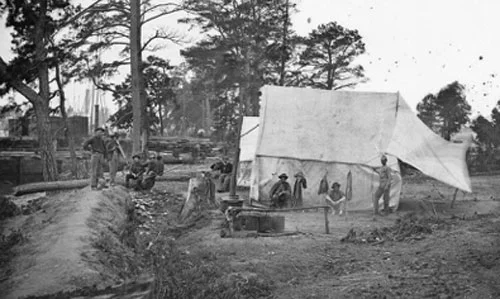

It was also common to see cooks hang pots from tripods. In the photograph here, the tripods were the same used for constructing Sibley style tents. Note the round socket at the top to support the vertical tent pole. Because of the tripod height, the pots hang by chains.

The previously unpublished, 1865 Quartermaster manual provides detailed descriptions of standard army equipment, including Sibley tent accouterments. Chains, specifically designated for kettles are described as “19/12 inches long, of 3/16 inch iron, galvanized, made with 21 twisted links, and a hook at each end; strong enough to support a weight of 45 pounds”(13)

But as seen in this detail from the camp of the Kentucky Orphan Brigade, not all tripods used by cooks were appropriated from Sibley tents:

Detail from “Confederate Camp” lithograph based on painting b Conrad Wise Chapman in 1861.(14)

Camp Stoves and Ovens

Camp cooking was not always done over an open fire. Civil War camps also display a variety of ovens and stoves.

When possible, the Army often sought to issue soldiers fresh bread, even providing mobile ovens for the purpose. These bakers load one such oven with bread:

A Government Oven on Wheels(15)

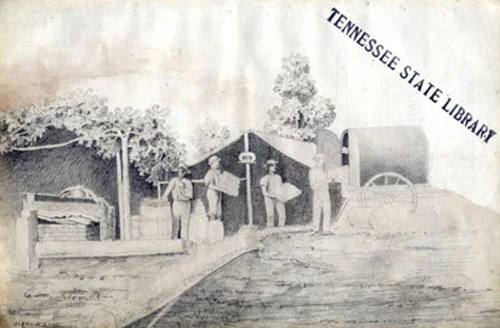

Sketch of Portable Army Oven(16)

This 1863 sketch from an engineer on General Sheridan’s staff shows a similar oven also being used for baking bread, seen here.

Capt. Sanderson describes a different army issued oven, advising soldiers that “[w]hen on hand for distribution, any regiment can obtain three or more ‘Shiras Ovens’ on requisition.”(17) He continues by listing all the additional baking equipment including rolling pins, a wooden peel, sieve and other items that would be provided with the oven.(18)

An article titled “‘Shiras ovens’ used during the War for the Rebellion” from a February 5, 1881 edition of the “Army and Navy Journal” provides more detail.(19) The ovens are described:

The body of each of these ovens is made of sheet iron, in two pieces, so curved that, when their upper edges are connected and the lower edges fixed in the ground, they form an arch. The lower edge of each sheet is bent outwards into a flange, so as to secure a firm rest on the ground. Transverse ribs of bar iron are riveted inside to strengthen the iron, and these ribs end in hooks and eyes, by which the sides are securely attached to each other along the ridge of the oven when erected. The front of the oven is closed by a two-handled iron door, which is kept in place by means of hooks and eyes. When the soil is of clay, or of other favorable quality, the rear end of the oven may be closed by the natural earth: but if it is sandy or loose, a sheet iron plate will be required to close it. No chimney is necessary. When set up, the whole, excepting the door, is covered with a mass of earth 8 inches in thickness.(20)

The article continues by outlining improvised versions to be made of dirt, by a few soldiers and completed in under an hour.(21) Depending on circumstances, soldiers would have used similar methods and sometimes salvaged materials such as bricks, dirt and metal.

The Alfred Waud Sketch below shows both a cook fire with a crossbar and an improvised oven. Identified as the “Camp of General Lewis Blenker”. This camp was probably located in Northern Virginia in November 1861.

“Thanksgiving in camp sketched Thursday 28th 1861” by Alfred Waud(22)

Detail

Detail

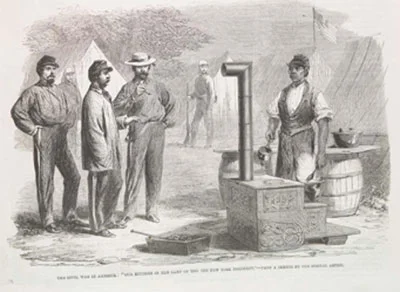

Sometimes civilian ovens found their way into camp. This cook uses a civilian stove, converted to field use. Notice the bent stove pipe which would have been fed into a chimney when used at home:

Our Kitchen in the Camp of the 2nd New York Regiment(23)

This unit had matching stoves in their Sibley tent camp. Also notice the kettle with handles in the bottom right. The cook uses a flipper to negotiate the various stove top frying pans.

Camp of 153d New York Infantry(24)

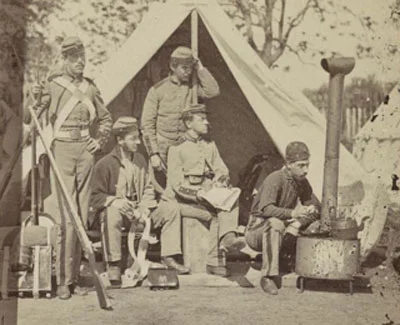

Here another stove is used by the highly documented 7th New York State Militia in their early war camp. Like the other examples, this would have been a great convenience but impractical for campaigning or cooking en masse.

7th N.Y. State Militia, Camp Cameron, D.C., 1861(25)

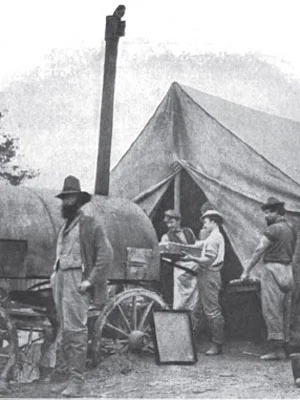

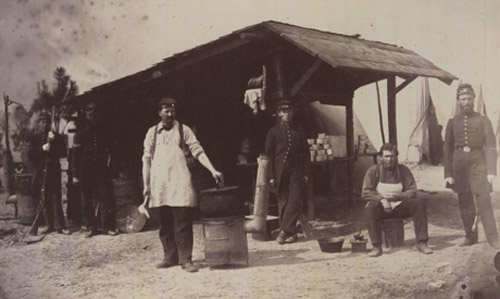

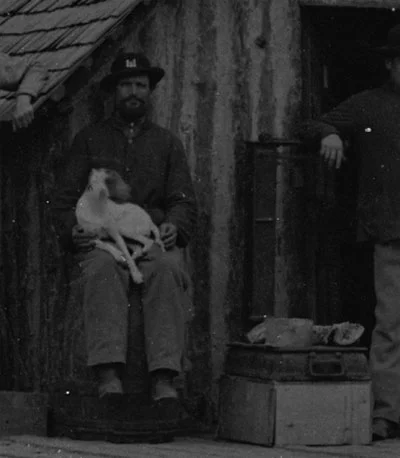

Below is a series of photographs depicting an odd style stove. I am not certain if these were manufactured or a unique item concocted by ingenious cooks. The bases may have been large stove pots. The setup on the right appears to have a lid. The soldier on the left has a meat fork or spoon and the one in the center holds a mess pan. On the far left of the image a gridiron hangs with dippers and other implements.

The Way they Cook Dinner in Camp(26)

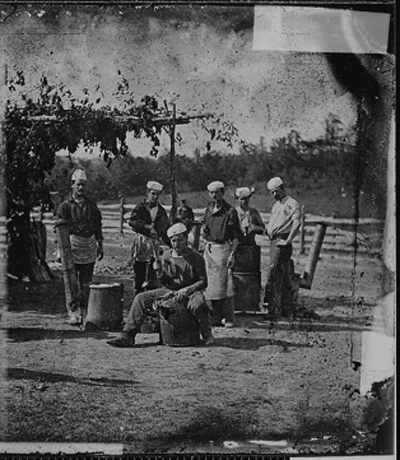

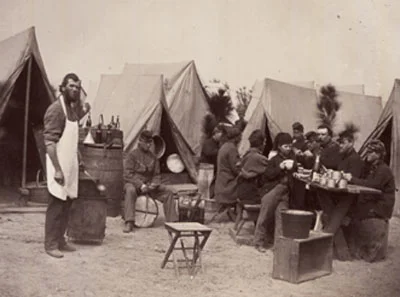

Another image of these unusual stoves. These also bear the side handles of stove top kettles and the stoves in the rear have small legs. In addition to aprons, these cooks have matching caps. Near the center of the frame rests a mess pan and ladle.

Camp Scene, camp cooks working(27)

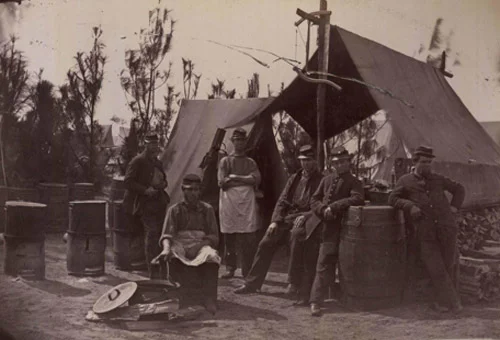

A series of photographs was taken of the 3rd New Hampshire’s 1862 Hilton Head camp. Fortunately for our purpose, the photographs included images of cooks for Company F, H, K and the “field music”. Three of the photographs display similar “kettle stoves” and are shown below. The fourth is examined later (footnote 35).

The stoves below also have small legs and stove pipes. Stove doors and hinges can be seen too. A large cast iron kettle sits on the stove. Also, notice the army mess pan and coffee grinder next to the seated cook. A mountain of tin cups covers the table behind him.

Cook’s galley, Company H, 3rd N.H. Infantry, Hilton Head, 1862(28)

Company K also used “stove kettles.” The seated cook holds a similar cast iron kettle and another coffee grinder sits on the barrel. Whatever was in the large barrel was valuable enough to require a hasp and lock. A large bow saw hangs from their tent poles.

Cook's galley, Company K, 3rd N.H. Infantry, Hilton Head, 1862(29)

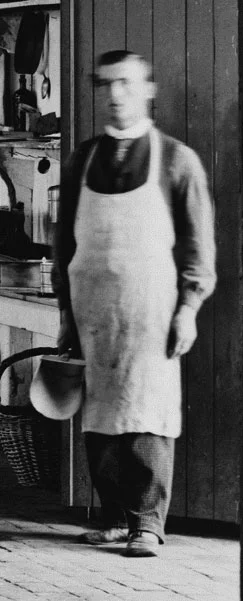

This aproned New Hampshire cook wields a large spoon and stands in front of another “kettle stove.” A wooden bucket sits in the foreground and a funnel and various bottles rest on the barrel behind him. This barrel also required a locking hasp.

‘Field Music’ of the 3rd New Hampshire Infantry.(30)

Commissary officer Brevet Lt. Col. J. Hathaway found that grates over the fire also served a useful purpose and in 1865 recommended that the Commissary Department provide them in the future:

“Richmond Mess”, Co A. 46th Va. Regt.(32)

I have found that what are known as Shaker gridirons, made of wire, are very convenient and useful to broil meats in ; they are light, very easily carried, not liable to get out of order, and would, in my opinion, be a decided acquisition to the cooking utensils now allowed.(31)

Other cast iron implements are found in Civil War camps. This watercolor by Private John Jacob Omenhausser depicts members of the 46th Virginia using dutch ovens for their cooking.

These images and sources give only a glimpse into techniques for cooking rations. As seen, they varied from simple to ingenious. Countless methods and variations were likely on display throughout the camps. However, it becomes clear that experience and the available tools led many cooks to employ similar methods.

Once they decided on the cooking method best suited for their circumstance, cooks needed to find the right tools for the job.

Equipment and Tools

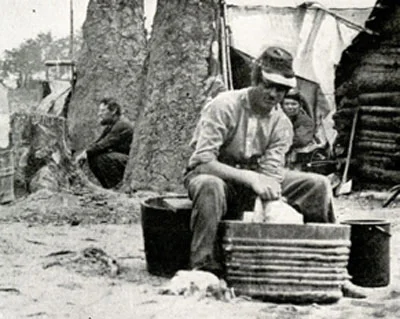

In “Camp Fires and Camp Cooking” Sanderson takes care to remind us, “[c]leanliness is next to godliness, both in persons and kettles.”(33) Not all cooks may have taken his advice, but many at least tried to keep their persons clean. In images, an apron often marks the cook and plenty are seen in Civil War camps.

Aprons

The next series of photographs shows company cooks wearing aprons. All appear similar - made from white cotton or linen, extend to the knees, tie around the waist and have a strap around the neck.

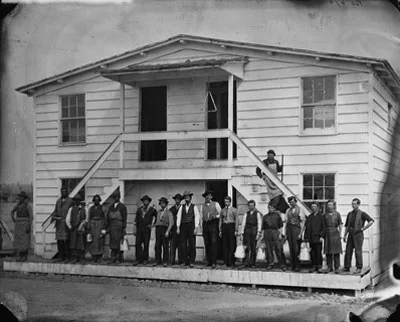

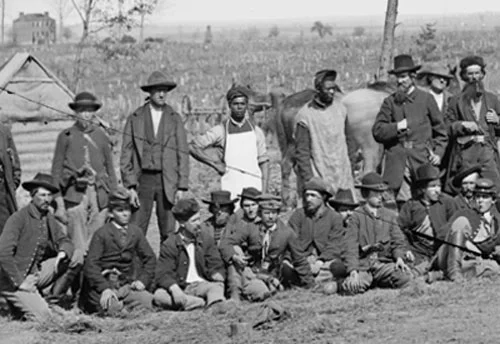

Some of the aprons in this photograph may be those of farriers. But the cooks on the left sport a combination of cotton and burlap aprons. The gentleman on the steps with the broom also wears a cook-style apron. Notice the numerous coffee pots, pans and even a few knives carried by his comrades. A dinner bell hangs from the porch roof.

Washington, District of Columbia. Mess house at government stables(34)

Detail

The photograph below is also the from the 1862 Hilton Head photographs of 3rd New Hampshire cooks (see images 28, 29 and 30). Like their comrades the Company F cooks also wear aprons:

Company F, 3rd N.H. Infantry and Cooks galley, Hilton Head, S.C.(35)

Though when aprons were not at hand, it appears some improvised to protect their uniforms. Notice the sack worn by one soldier and the use of bricks to support the camp kettle. The soldier on the right is standing in front of a small coffee pot:

Detail from Camp Scene.(36)

Clearly these cooks were also short an apron:

Detail from: Brandy Station, Va. Scouts and guides of the Army of the Potomac.(37)

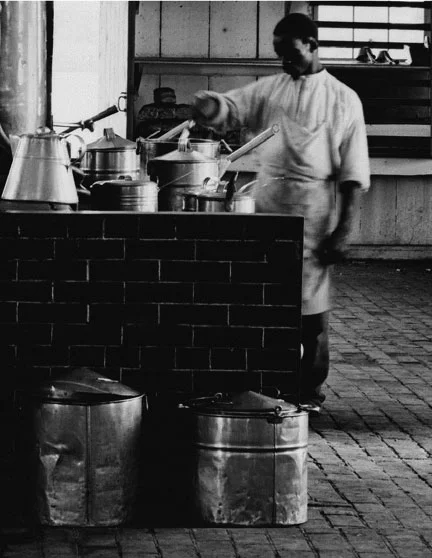

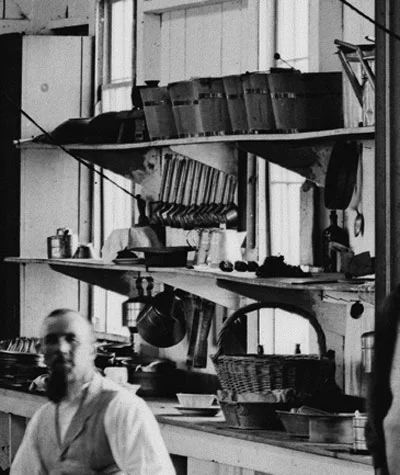

This indoor kitchen displays many amenities. This kitchen was built to cook for hundreds or thousands of soldiers. It was located near the junction of the Orange and Alexandria Railroads. A photograph of the facility can be seen below.

Much of the equipment in this kitchen would not have been available to cooks in the field, even in permanent camps. However, we still find common items around the room and the cooks’ aprons are the same style shown above.

Alexandria, Va. Cooks in the kitchen of Soldiers' Rest(38)

Details:

This cook has his hands full with numerous pots and kettles on an impressive stove. Notice the variety of lids and handles. Also note the bails ears and handles of the large kettle on the floor. These vary from the simplified style seen in most camps.

The cook near the doorway holds a large tin scoop and the shelves are brimming with useful culinary tools, often the same used by their campaigning counterparts.

A meat fork hangs at left and there is no shortage of dippers. You can imagine the number of soldiers they would feed with this much equipment.

Three kettles rest on the rear shelf. Notice the handles that are not present on kettles seen in the field. These are meant for a stove top, not a campfire.

In case they run short, more dippers. Wooden buckets, coffee pots and mess pans all stand at attention. Judging by the size of the complex, you can understand their arsenal of equipment:

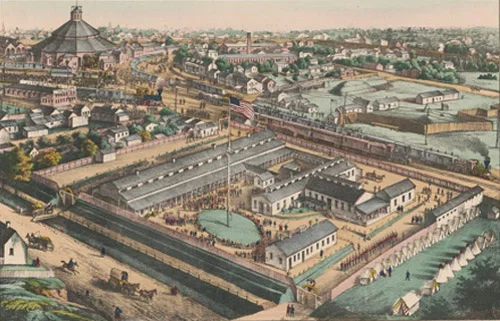

Soldier's Rest, Alexandria, Va., commanded by Capt. John J. Hoff.(39)

Now that we have identified some cooks in the field, we need to find the tools they used to cook and issue their fare. The “Soldier’s Rest” photo is a great starting point. But how did this equipment differ from that used by regimental and brigade commissaries in the field?

Cooking Vessels

The most essential equipment for any camp cook was a cooking pot. In the vast majority of the photos large kettles were utilized. Frying pans often can be found in Civil War camps, but are often personal items. Large frying pans were used, but when cooking for so many, cooking pots seem preferred.

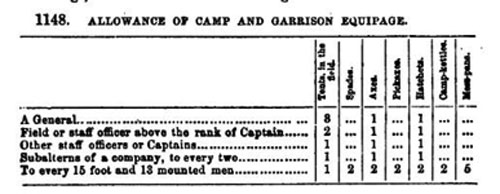

Article XLII of the 1861 U.S. Army Regulations provides a chart outlining kettles and mess pans allotted to troops:(40)

This same chart and information was published at Section 1031-32 of the 1864 Confederate Regulations Manual.(41)

Writing to the Commissary Department on August 14, 1865 about his command, Brevet Lieutenant Colonel, John L. Hathaway confirms that kettles and pans were not only regulation but practice: “In camp, camp kettles and mess pans are used (the allowance being five mess pans and two camp kettles to every 15 foot or 13 mounted men), in which soups and coffee may be made and meats boiled or fried.”(42)

Camp Kettles

Closely examining photographs and sketches of camp cooking, confirms that camp kettles were standard fare in Union camps from Brandy Station to Hilton Head.

In “Camp Fires and Camp Cooking” Sanderson tells us that Army camp kettles should be, “made of iron, with a handle, and varying in size from four to seven gallons, (they should be made so as to have one slide into the other, in nests of four)”(43) But the 1865 Quartermaster manual provides even more detail:

Camp Kettles, - to be of 3 sizes, made of good American sheet iron, and so as to fit into each other in nests of three, viz: - No.1, the largest size, should be 12 inches diameter and 11 ¾ inches deep, and to contain 4 ½ gallons. No. 2, to be 10 ¼ inches diameter, 11 ½ inches deep, and to contain 3 ½ gallons. No. 3, to be 9 ½ inches diameter, 11 ¼ inches deep, and to contain 2 ½ gallons. All to have iron wire bails, 5-16 of an inch diameter, the ends of which to be drawn down to a point. Weight of a nest of three kettles, 17 ¼ to 17 ½ pounds.(44)

In 1901 the U.S. Government Printing Office published, “How to Feed an Army” which collected remembrances, and techniques of Civil War commissary officers. Contributing to that work, Capt. N. J. Sappington, Commissary Officer in Elmira, New York also agreed that camp kettles were the cornerstone of field cooking, writing in June 1865 that:

[f]or field service the simplest cooking utensils, and the fewest that can be made to answer, are the best. A few camp kettles of about 5 gallons capacity and a frying pan or two is all that are needed for each company, and can be carried slung under the wagons, or on a mule.(45)

Images confirm these descriptions, showing nearly universal features and construction. As described, size varies, but almost all camp kettles are made from sheet metal with a rolled lip, folded bottom and one seam running vertically on the side. As explained in the Quartermaster Manual, a heavy bail handle completes the kettle.

Several photos of cooking kettles are shown below, but additional examples are seen in the section of this article that addresses campfire cooking.

White House Landing, Pamunkey River(46)

In this close-up, an array of camp equipment is seen. Several of the standard bail camp kettles are in use. Note their heavy construction and sturdy bail handles. Unlike the stove top counterparts shown in the “Soldier’s Rest” photo, these do not have side handles or bail ears - just punched holes and a strong loop handle. Also seen is a small frying pan. Behind, a large kettle in a spider stand serves as a stove. This may have been a unique item or field modified. A shallow dipper sits on the stove top.(47)

This soldier washes his clothing in a wooden bucket next to a camp kettle. A second kettle is seen resting near the axe:

Washday in Winter-Quarters(48)

The camp kettle was not only to be found in Union camps. In this 1861 sketch, members of the “Crescent City Mess” hover over a fire, awaiting their food. The soldier at right holds a smaller camp kettle or bucket. At left, mess pans are in use, along with various other mess equipment.

Crescent City Mess by Private James H. Smith, Co. 3, 6th Louisiana Infantry(49)

Cast Iron Kettles

Section 1149 of the U.S. Army Regulations states that ‘iron kettles’ may be issued to troops in garrison, rather than camp kettles.(50) As with the kettles, the 1865 Quartermaster manual provides more detail, describing them as follows:

Iron Pots, - to be of cast iron, No. 9; diameter outside at top, 15 ? inches; depth inside, 11 ½ inches, with three legs on bottom, 3 ½ inches long; lug or ear on opposite sides of top, for the bail; the bail to be of round iron wire, 7-16 of an inch diameter. Weight of pot, complete, 35 to 37 pounds, and to contain six gallons.(51)

Not all match that description, but many iron kettles are found in Civil War camps. The kettle below rests on three tiny legs. The pot has looped ears to hold the handle. It also has raised rings around the belly of the pot. This is a common feature.

Camp of the 71st New York Vols., Cook House Soldiers Getting Dinner Ready(52)

Confederate Troops also used similar cast iron kettles. This detail from a July 1861 Harper’s Weekly engraving shows Confederates near Manassas Junction using a large inventory of cast iron kettles and the familiar cross-bar cooking method:

General Beauregard's Camp of Confederate Troops at White Springs, Virginia, Near the Manassas Gap Railroad(53)

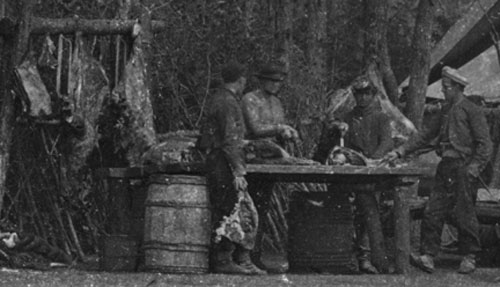

Near Charleston, South Carolina, these cooks also work to prepare a meal for Confederate soldiers using the same method. Though their kettles spider leg cast-iron kettle seems much smaller.

Near Charleston.(54)

Not all commissary officers fully appreciated camp kettles. Complaining to the Commissary Department in August 1865, Chief Commissary for the District of Southwest Virginia, Capt. S. S. Patterson criticized the kettles’ function during a campaign:

On the march all cooking utensils should be left, except those for headquarters. Soldiers of the line will cook for themselves, with no utensils except a knife, sometimes a skillet. Camp kettles are here worse than useless, and are usually hung in great knots under the wagons, whence many are dragged off and lost, for nobody uses them unless some of the train guard may muster up energy enough to untie one when there are more potatoes and onions on the train than they like to eat raw. They are carried simply and only because the quartermaster must account for them.(55)

The rigors of campaign certainly did not always make kettles and wagon trains accessible, but I doubt the enlisted men would have appreciated Captain Patterson’s double standard. But even he conceded that in garrison, cooks were essential.(56)

Mess Pans

Issued alongside the kettles was the utilitarian mess pan. Mentioned in the 1861 U.S. Regulations, they are also described in detail by the 1865 Quartermaster Manual:

Mess pans, - to be made of good American sheet iron, 11 ½ inches diameter at top, and 8 ½ inches at the bottom, 5 ¼ inches deep; to contain 5 quarts. Weight about 2 pounds.(57)

These pans can be found throughout Union Army camps. Once you are looking for them, you recognize these pans instantly.

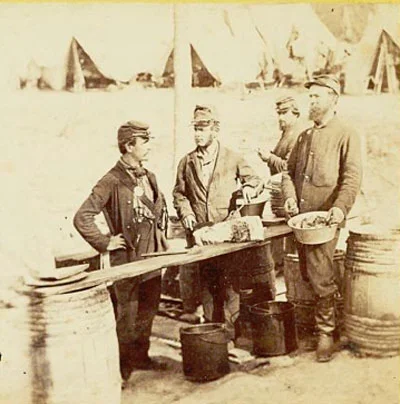

In this stereoview image the man on the right holds a mess pan with handles. Another pan rests behind him to the left. Also, we see the gentlemen in the center has a meat fork and butcher knife. Notice the camp kettles in the foreground.

Preparing the Mess(58)

This iconic 1861 photo shows two mess pans, along with other cooking equipment including a large spoon, coffee pot, wooden bucket and meat saw. It even appears the soldiers in the rear are guarding a crossbar style cook fire:

Camp of the 31st Pennsylvania(59)

Here Gilbert Thompson, who served as an engineer with the Army of the Potomac, captured his unit’s “Cook Tent” in this sketch from his journal. A pile of mess pans appears to be lying at right. Also visible are barrels, a cracker box and possibly a tripod near the tent entrance. The kettles hang above the fire using S hooks.

Our Cook Tent, White House Landing(60)

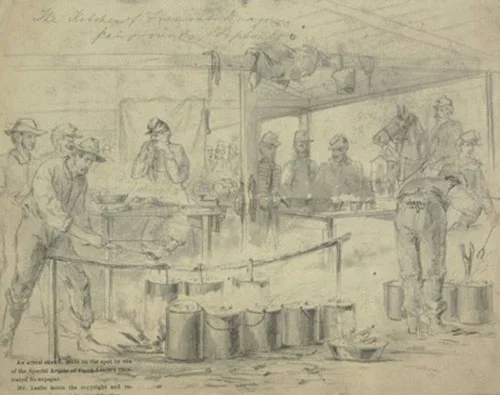

Notice more mess pans in the sketch below. Also recognize the same open fire cooking method, guarded by the cooks armed with meat forks. This sketch was published as an engraving in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, No. 310 - Vol. XII, November 2, 1861.

Kitchen of the Fremont Dragoons, Fairgrounds, Tipton MO, October 13, 1861(61)

Additional Equipment

Circumstance would not have allowed all regimental and brigade commissaries to always have the necessary equipment. But, original sources show a surprising consistency on this subject:

The standard supply of ... property for use of a brigade commissary in the field is as follows: One field table, one field desk, one platform scale; one spring balance complete; one commissary chest, containing spring balance, two liquid measures, two metal faucets, one funnel, one molasses gate, one scoop, one cleaver, one hatchet, one meat saw, one meat hook, four butcher knives, one butcher steel, one tap borer.(62)

Capt. Sappington agreed and enumerated the different equipment needed between the brigade and regimental commissary:

[F]or commissary property it is best to dispense with all unnecessary tools; anything but what is in constant use is soon lost or destroyed. The following articles are enough to do the issuing to a corps or brigade : One platform scale, one small beam or spring balance scale with large dish, about four scoops, two funnels, two hatchets, two faucets, one meat saw, one cleaver, one butcher steel, and four butcher knives, … [F]or each regiment or separate command of the corps or brigade, one spring balance, three scoops, one cleaver, one meat saw, and two or three butcher knives to make the net issues of stores received in bulk from the corps or brigade commissary.(63)

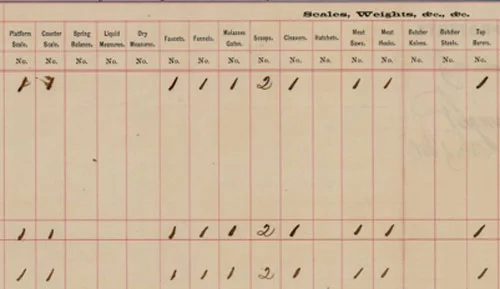

Wartime Paperwork confirms these officers’ lists. A form entitled “Return of Commissary Property Received, Issued and Remaining” from the 75th Indiana during their November 1863 stay at Chattanooga, Tennessee, shows nearly the same items:(64)

The 75th Indiana’s Commissary form was more detailed, but similar to “Form 12” provided in the 1855 U.S. Regulations for Subsistence.(65)

Distributing government rations with accuracy was a foremost concern and it is fitting that scales are the first items listed by these inventories. The 1855 U.S. Subsistence Regulations outline the anticipated ration waste. These Regulations accounted for no more than 10 percent waste for items such as pork, bacon, sugar, vinegar and soap. While no more than five percent of waste was permitted on dry goods, including hardtack, beans, rice, coffee and salt.(66) Any waste exceeding this was to be accounted for monthly.

With strict standards on waste and emphasis on accuracy, it is fitting that both a “Spring Scale” and “Platform Scale” were part of a unit’s commissary equipment. Examples of both can be found in the photographs and sketches below.

Platform Scales, Spring Scales, and Measures

Commissary Tent at Headquarters of the Army of the Potomac near Fairfax Court House Va, June 1863(67)

Detail

The platform scale seems to be a standardized item. Very similar scales are seen in the Brandy Station photos, and others below. However the next two images show a compact variant.

View of the Quartermaster's Store House, 159th Regiment New York, January 1, 1865(68)

Of note is the platform scale matching that found in the engraving below. Also interesting in this image are the colorful signs that adorn the storehouse.

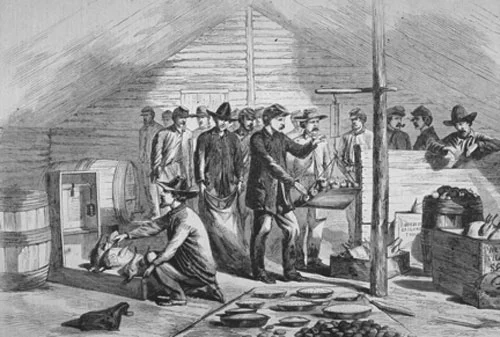

Notice the use of both the compact platform scale and the spring scale in the engraving below:

5th and 9th Corps receiving Thanksgiving rations in 1864.(69)

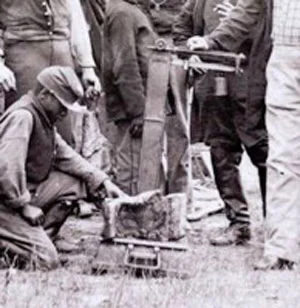

In this great photo, we see the soldier on the right holding a hook of meat in a spring scale. Also present in the center are a meat saw and butcher knife.

Weighing Out the Rations(70)

Undoubtedly both types of scales were used by commissaries. But offering his suggestions to the Commissary Department, Capt. Patterson writes that:

In camp and at a "post" the army platform scales are useful, but on a march they get out of order, are clumsy and heavy to transport, hard to load and unload, can not be carried readily short distances by hand, and are consequently behind time in an actual campaign. Of all the platform scales that accompanied the marches up and down the valley of the Shenandoah scarcely one was habitually used. The 30-pound spring balances did the work ; these are not heavy enough, and the scale dish makes them very inconvenient, as it will not hold enough and its chains are constantly in the way and tangling, for the scale can not always be hung up, but must be held in the hand, and laid down again. If they were made to draw 50 pounds, that would be sufficient to break readily all ordinary packages at one or two drafts. The scale should balance at zero, so as to weigh meats quickly and conveniently, hanging them on the hook, while for other things a tin pail is far better than the dish.(71)

Scales were commonplace when distributing Civil War rations. But not all of them were used to distribute rations accurately, as relayed in this anecdote from Newton Coker, Commissary Sergeant of the 39th Georgia:

When I would go to the division slaughter pen to get our supply of beef, the man ... would say to me, “Sergeant, you must weigh your own beef.”... I would cut up considerably about it, but would go ahead and weigh the beef. In fact it was just what I wanted to do.

The division commissary clerk would seat himself by a tree … with his book and pencil, and as I weighed a quarter of beef, if it weighed, say 75 pounds, I would sing out, “60 pounds.” If it weighed 90, I would call out, “70 pounds,” and so on.(72)

Coker also mentions carrying steelyard scales through significant portions of the war as part of his commissary responsibilities. Though at one point, he abandoned his steelyard for a musket and cartridge box.(73)

Scales were not the only item used to accurately portion rations. Both Confederate and Federal armies provided their commissary soldiers with measures to facilitate distribution.(74) This included both dry and liquid measures. Confederate Regulations provided dimensions for wooden boxes to serve as dry measures for a quart, half gallon, peck, bushels and a barrel.(75) Liquid measures, likely tin, were also provided and are discussed further below.

Meat Saws, Butcher Knives, Scoops, and Commissary Chests

The lists provided by the commissary officers and the 75th Indiana’s commissary return provide great insight into additional equipment carried by commissary soldiers. But Capt. Patterson distinguishes the extra equipment needed by the regimental commissary:

For a brigade, one 50-pound spring balance and two gallon tin pails; one scoop; one ax and helve, fitted; one hatchet and one claw hammer; one gallon measure; one meat saw; one cleaver; one tap borer ;one meat hook one butcher's steel; one molasses gate; one faucet, and four butcher knives… For each regiment the same, except measure, molasses gate, faucet, and two butcher knives.(76)

Ever willing to provide suggestions, Patterson also outlines commentary on each item:

The gallon measure should be marked for a pint, a quart, 2 quarts, and 3 quarts. One measure is better than two or more ; in all things simplicity is a great object and especially in the number of things a person must look after on a march — handle, pack, and unpack.

The quart measure is not large enough to expedite the issue of vinegar, molasses, and whisky. In camp it may be expedient to have more than one, for you may wish to use several at once, but in the field one measure, one gate, and one faucet are all you will have occasion to use, and is much more likely to stay in your hands than if you should provide for losing one by furnishing two.

The tap-borer is all-sufficient without the gimlet, which is a dead weight to a commissary.

The funnel might be worth something if it were not every way too large; the nozzle should be not over a half inch in diameter and more deeply corrugated than it is;the body of the funnel is much too full.

The faucet should be a good one, that will not leak more at the handle than at the vent. Out of a whole set of common faucets you can not find one fit to draw vinegar, much less whisky.

The butcher knives should be well ground and sharpened. No dry measure is wanted ; everything can be weighed.(77)

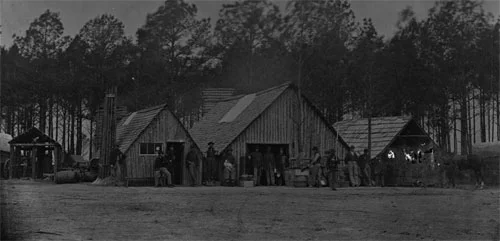

A series of photos depicting an engineering regiment’s commissary at Brandy Station in 1864 contains many of those addressed above. These photos are the best representation of Commissary equipment in the field that I have yet found.

Brandy Station, Va.(78)

In this image, a soldier dispenses dry goods into a scale with a tin scoop. A platform scale is next to the doorway on a cracker box. Another soldier dons an apron and prepares to use his meat saw on a makeshift table. Hopefully he did not get any cigar ash in the rations.

Detail

The handle of a butcher knife or cleaver is seen on the table top and a box of candles rests by the tree. Another soldier, possibly an officer, holds a large sack and awaits his unit’s allotment.

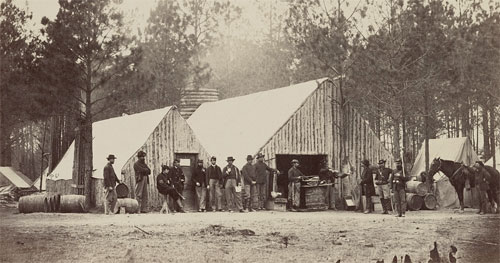

A second photo of this camp reveals even more of the same equipment mentioned by the 75th Indiana’s 1863 Quartermaster Inventory. This photo appears to have been taken at a later date as the tent on the right has turned into a building, all the buildings have traded cloth roofs for shingles and a window has been added to the building on the left. Still, several of the same soldiers remain.

Brandy Station, Va.(79)

Details:

The same spring scale and pan hang, and the nearby soldier holds the familiar tin scoop. A cracker box has been converted to a table and a different soldier carves up the meat. His supervisor looks on anxiously with paperwork in hand. You can also note a butcher knife sticking up from the table and handwritten label on the barrel of “Beans”.

The same platform scale is next to the doorway but this time the unit has a dog posing with them.

A second platform scale hides behind these barrels:

The real gem of the photo is an open commissary chest, next to the box of candles. We can see a butcher knife, a sharpening steel and a second meat saw. Likely this chest contained items such as the funnels, scoops, molasses gates, faucets and tap borers referenced in the 75th Indiana Commissary returns and commissary officers’ commentary.

Though unfamiliar to us, we can see by the numerous barrels why items such as tap borers, faucets and gates would be important for these soldiers’ work.

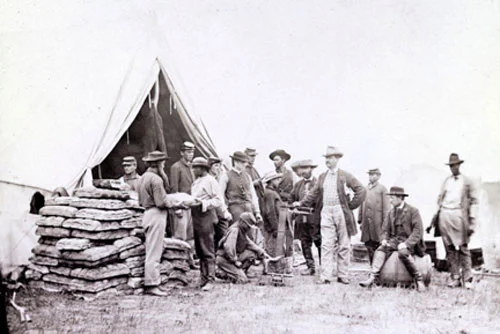

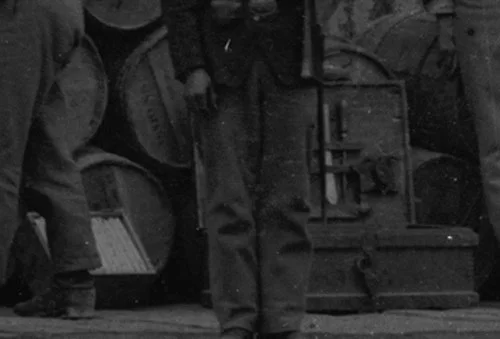

A third photo in this series, taken in a different location, shows more troops at Brandy Station portioning meat for distribution.

Brandy Station Commissary Dept.(80)

A platform scale is peeking from behind these soldiers and barrels. Detail:

Non-Issued Equipment

The equipment provided by the Commissary Department left some cooks wanting. In “Camp Fires and Camp Cooking” Sanderson adds that the company,

[b]esides the allowance from government, however, the company cooks should be furnished, from the “Company Fund,” with two large iron spoons, two large iron forks, two stout knives, one tin cullender [sic], and one yard of flannel; also a false tin bottom, closely fitting the kettles;(81)

Other commissary officers also recognized the need for additional tools. Capt. N. J. Sappington noted that “All companies will supply themselves with whatever else is needed, and some have within my knowledge provided even them at a cost of over $60 to each company for the total outfit rather than forego the privileges of such an arrangement.”(82)

In recommending to the Commissary Department the needs of butchers at an army slaughterhouse, Brevet Col. M.R. Morgan listed equipment that included, axes, butcher saws, three butcher knives, a sharpening steel per butcher, shovels, spades, picks, brooms and “scrubbing brushes with handles.”(83) Certainly the needs of butchers may have differed from a regimental or brigade commissary. But overlapped too.

The need for tools to negotiate the various containers and packages was explained by Capt. Sappington:

A commissary must have an ax, and it should be furnished as commissary property, because it is so difficult to get one from a quartermaster. The hatchet should be without the cleft for drawing nails, which is entirely useless, and instead a claw hammer should be furnished for pulling and driving nails and mending broken packages.

Many of these tools are seen in the photos previously discussed and would have been available in Civil War camps, if not always supplied to cooks and commissaries by the proper authorities.

Conclusion

Much focus has been placed on the study of how soldiers cooked and carried their rations. But the marching ration was an exception not the rule. As has often been discussed, campaigns were numerous for the Civil War soldier, but they were not commonplace. Consequently, many meals were consumed on the march or from the haversack. But most soldiers’ meals came from the cook and the commissary.

In examining the methods and tools of camp cooks and commissaries, similarities abound. Standardized equipment can be seen in Union Army units from Hilton Head to Brandy Station and often conform with government regulations. Circumstances or individual creativity may have provided unique opportunities, but common trends are on display in these images.

A lack of resources makes it difficult to draw similar conclusions for their Confederate counterparts. But the limited resources confirm that many trends spanned the picket line.

Through these images and documentary sources, the constant focus on consistency, accuracy and efficiency may come as a surprise. But these sources only show a glimpse into the government's task of feeding armies. Considering the cost and scope it is not surprising that soldiers employed scales, measuring tools and standardized equipment. It is also fitting that their officers devoted exhaustive energy and constant evaluation to perfecting their subsistence craft, all with an eye toward efficiency.

But for the soldier in the field, these were not his problems. All that likely mattered was the skill of his cook and the quality and quantity of his rations. In his handy 1862 guide, Sanderson provides his “Kitchen Philosophy” - applicable to both the casual and professional cook, whether in the army or the kitchen:

Remember that beans, badly boiled, kill more than bullets; and fat is more fatal than powder. In cooking, more than in anything else in this world, always make haste slowly. One hour too much is vastly better than five minutes too little, with rare exceptions. A big fire scorches your soup, burns your face, and crisps your temper. Skim, simmer, and scour, are the true secrets of good cooking.(84)

**Special Thanks to Charlie Thayer, Michael Clarke, Mark Susnis and Craig Schneider for their time, advice, and resources.

Footnotes

Patterson, Capt. S. S. in How to Feed an Army. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1901), 152. Accessed December 15, 2016. https://books.google.com/books?id=py4tAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=how+to+feed+an+army&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj8gp_-_vLQAhWF7yYKHeFABLAQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=drill&f=false.

Sanderson, Capt. James M. Camp Fires and Camp Cooking. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1862). Accessed December 15, 2016.

https://books.google.com/books?id=QiBXAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=camp+fires+and+camp+cooking&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjk3O_PifnQAhVIiSwKHTZGD48Q6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=camp%20fires%20and%20camp%20cooking&f=false.Stacy, George. Fortress Monroe, Col. Duryee’s Zouaves. 1861. Gotthiem Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2009630923/.

O’Sullivan, Timothy. Petersburg, Va. Sutler's bomb-proof "Fruit and Oyster House. 1864 or 1865. Selected Civil War Photographs, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/cwp2003000574/PP/.

Capt. Ballerman’s Kitchen: Tasting the Soup. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Library of Congress. Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003004792/PP/.

Waud, Alfred. Detail from Harrison’s Landing. 1862. Morgan collection of Civil War drawings, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004660833/.

Forbes, Edwin. Our Kitchen Near Beverly Ford. Aug. 26, 1863. Drawings (Documentary), Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/civwar/item/2004661939/.

Gifford, Sanford Robinson. The Camp of the Seventh Regiment near Frederick, Maryland. 1861. New York State Museum.

Ellsworth’s Soldiers in Camp. Harper’s Weekly. Vol V, No. 232. June 8, 1861. (available online at: http://www.sonofthesouth.net/leefoundation/civil-war/1861/june/soldiers-in-camp.htm).

Brady, Matthew. Cooks’ quarters. Record Group 111: Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860 - 1985. National Archives, Washington D.C. https://research.archives.gov/id/524689

Waud, Alfred. Bivouaced in the rifle pits 5th corps. July 1864. Drawings (Documentary), Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004660819/.

City Point, Va. African American army cook at work. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Library of Congress. Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/civwar/item/cwp2003000544/PP/.

Crosman, George H. The 1865 Quartermaster Manual, ed. Earl J. Coates and Frederick C. Gaede (Gettysburg: Arbor House Publishing, 2013) 254.

Confederate camp during the late American War. 1871. Civil War Prints and Photographs. Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/civwar/item/2006686265/resource/

A Government Oven on Wheels. ed. Robert S. Lanier. The Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes, Volume 8. 51. New York: The Review of Reviews Co., 1911. https://archive.org/details/millersphotographic08franrich.

Fields Notes of Major Francis Mohrhardt as an Army Engineer in Tennessee During the Civil War. 1863. Historical Maps Collection. Tennessee State Library and Archives.

Sanderson at 12.

Ibid.

Bread for the Army, Army and Navy Journal. Volume XVIII, Number 27. 553. (available online at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924069761603;view=1up;seq=545.)

Ibid.

Ibid.

Waud, Alfred. Thanksgiving in camp sketched Thursday 28th 1861. Drawings (documentary). Library of Congress. Washington D.C. Accessed on December 14, 2016. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004660226/.

Our Kitchen in the Camp of the 2nd New York Regiment. London Illustrated. Vol. 38, No. 1096. June 29, 1861. http://iln.digitalscholarship.emory.edu/browse/iln38.1096.164/.

Camp of 153d New York Infantry. 1861. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012649030/.

7th N.Y. State Militia, Camp Cameron, D.C. 1861. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Accessed December 12, 2016. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2013648451/.

Roche, T. C. The Way they Cook Dinner in Camp. Civil War stereographs, 1861-1865. New-York Historical Society. Accessed January 15th 2017. http://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p16694coll47/id/1780

Brady, Matthew. Camp Scene, camp cooks working. Record Group 111: Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860 - 1985. National Archives, Washington D.C. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/529421.

Cook’s Galley, Company H, 3rd N.H. Infantry, Hilton Head. 1862. Massachusetts Civil War Photograph Collection, Volume 21. United States Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle. Accessed on February 6, 2017. http://cdm16635.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16635coll12/id/10140/show/10115/rec/41.

Cook’s Galley, Company K, 3rd New Hampshire, Hilton Head. 1862. Massachusetts Civil War Photograph Collection, Volume 21. United States Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle. Accessed on February 6, 2017. http://cdm16635.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16635coll12/id/10087/show/10062/rec/5.

‘Field Music’ of the 3rd New Hampshire Infantry. Feb. 28, 1862. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Accessed December 12, 2016. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003655415/.

Hathaway, Lt. Col. J. L. in How to Feed an Army (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901): 29. https://books.google.com/books?id=py4tAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=how+to+feed+an+army+book&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiRopCT--7QAhWCthoKHfKXD04Q6AEIGjAA#v=onepage&q=how%20to%20feed%20an%20army%20book&f=false.

Omenhauser, John J. Richmond Mess. Camp Worron’s / New Kent cty. R.L.I. Blues. 1863. Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond Va. In Soldier Art. Richmond: Museum of the Confederacy, 2006.

Sanderson. Camp Fires and Camp Cooking: 4.

Washington, District of Columbia. Mess house at government stables. April, 1865. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Accessed December 12, 2016. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cwpb.04128/?co=civwar.

Company F, 3rd N.H. Infantry and Cook’s galley, Hilton Head, S.C. 1862. MOLLUS - Mass Civil War Photograph Collection, Volume 21. United States Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle. Accessed February 6, 2017. http://cdm16635.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16635coll12/id/10140/show/10113/rec/121.

Brandy Station, Va. Scouts and guides of the Army of the Potomac. March, 1864. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Accessed December 12, 2016. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003000269/PP/

Alexandria, Va. Cooks in the kitchen of Soldiers’ Rest. April, 1865. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Accessed December 12, 2016. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/civwar/item/cwp2003000931/PP/.

Soldier’s Rest, Alexandria, Va. 1864. Civil War Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/civwar/item/2003671607/resource/

Revised United States Army Regulations of 1861. (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1863): 169. https://books.google.com/books?id=_G4DAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Regulations for the army of the Confederate States, 1864. (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1864): 106. https://openlibrary.org/works/OL15374910W/Regulations_for_the_army_of_the_Confederate_States_1864.

Hathaway in How to Feed an Army: 29.

Sanderson, Cpt. James M. Camp Fires and Camp Cooking (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1862): 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=QiBXAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=camp+fires+and+cook+fires&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj4qLqN4fLQAhVnDcAKHW-zA_8Q6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=camp%20fires%20and%20cook%20fires&f=false.

George H. Crosman, The 1865 Quartermaster Manual, ed. Earl J. Coates and Frederick C. Gaede (Gettysburg, PA. Arbor House Publishing, 2013), 214.

Sappington, Capt. N.J.. in How to Feed an Army: 61.

White House Landing, Pamunkey River. 1861. Civil War Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Accessed December 14, 2016. https://www.loc.gov/item/2012649526/.

Ibid.

Washday in Winter-Quarters. Lanier, Robert S., ed. The Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes, Volume 8: Soldier Life and Secret Service. 187. New York: The Review of Reviews Co., 1911. Accessed on December 13, 2016. https://archive.org/details/millersphotographic08franrich.

Smith, James H. Crescent City Mess. 1861. Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond Va. In Soldier Art. Richmond: Museum of the Confederacy, 2006.

Revised United States Army Regulations of 1861, p. 169.

George H. Crosman, The 1865 Quartermaster Manual, ed. Earl J. Coates and Frederick C. Gaede (Gettysburg: Arbor House Publishing, 2013), 214.

Camp of 71st New Vols. Cook house Soldiers getting dinner ready. 1861. Civil War Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/civwar/item/cwp2003004790/PP/.

General Beauregard's Camp of Confederate Troops at White Springs, Virginia. Harper’s Weekly. Vol V, No. 237. July 13, 1861. (available online at: http://www.sonofthesouth.net/leefoundation/civil-war/1861/july/white-springs-virginia.htm).

http://npshistory.com/publications/civil_war_series/2/sec6.htm

Capt. S. S. Patterson. in How to Feed an Army, p. 151-2.

Ibid.

George H. Crosman, The 1865 Quartermaster Manual, ed. Earl J. Coates and Frederick C. Gaede (Gettysburg, PA. Arbor House Publishing, 2013), 214.

Roche, T.C., Preparing the Mess. Civil War Photographs Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010648602/.

Camp of 31st Pennsylvania Infantry near Washington, D.C. 1861. Civil War Photographs Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/98507952/.

Thompson, Gilbert. Our Cook Tent, White House Landing. Gilbert Thompson Journal, Image 96. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss95752.01/?st=gallery&c=160.

Kitchen of the Fremont Dragoons, Fairgrounds, Tipton MO, October 13, 1861. Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. New York Public Library, New York.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6eaed3cc-7576-1df6-e040-e00a18065bf1.Hathaway in How to Feed an Army. 30-31.

Sappington in How to Feed an Army. 61.

Return of commissary property received, issued, and remaining of the 75th Indiana Infantry. November 13, 1863. Civil War Military Records, Tennessee State Library and Archives. Accessed on December 13, 2016. http://teva.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15138coll9/id/93.

Regulations for the Subsistence Department of the Army of the United States. (Washington: A.O.P. Nicholson, 1855), 24. Available online at: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=y0YsAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA24.

Regulations for the Subsistence Department of the Army of the United States. (Washington: A.O.P. Nicholson, 1855), 5. Available online at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1qujy70KmjOupdOaniMnhXAKW98r1p9tZlal1XF6ErVc/edit.

Commissary tent at headquarters of the Army of the Potomac, near Fairfax Court House, Va. June 1863. Civil War Photographs Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012650157/.

View of the Quartermaster's Store House, 159th Regiment New York, ca. 1865. George Eastman House, Getty Images.

Troops receiving Thanksgiving rations, November 1, 1864. (Photo by Kean Collection/Archive Photos/Getty Images) http://www.gettyimages.fr/license/102995535

Commissary Stores at Camp Essex, Weighing out the Rations. Published by E. & H. T. Anthony & Co. New York. War Views, No. 823.

Patterson, How to Feed an Army. 153.

Coker, Newton. The War As I Saw It. ed. by Gerald D. Hodge, Jr., 2011. p. 163.

Coker, p. 67.

Patterson, How to Feed an Army. 153. and Regulations for the army of the Confederate States, 1863. 1141, notes 8-12 (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1863): 131.

Regulations for the army of the Confederate States, pp 131-2.

Patterson, How to Feed an Army. 153.

Ibid. 153-154.

O’Sullivan, Timothy. Headquarters Army of Potomac - Brandy Station. Commissary Storehouse. 1864. Civil War Photographs Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Accessed December 14, 2016. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012649000/resource/.

Petersburg, Va. General view of the commissary department, 50th New York Engineers. 1864. Civil War Photographs Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Accessed December 14, 2016. https://www.loc.gov/item/cwp2003000586/PP/. (Author’s Note: This photograph is potentially misidentified by the Library of Congress as “Petersburg”. The buildings and soldiers are the same depicted in the previous image identified as “Brandy Station, February 1864” and attributed to Timothy O’Sullivan. If the 50th New York Engineer identification is correct, they were stationed at Rappahannock Station, “about two miles from Brandy Station” in February 1864. During this period photographs of the regiment’s camp were taken. See, p. 22 of “The Letters and Diary of Thomas James Owen” (1985), available online at http://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Publications/EngineerPamphlets/EP_870-1-16.pdf.

Brandy Station, Va. Commissary Department - Army of the Potomac Headquarters, 1864. Civil War Photographs Collection, Library of Congress, Washington D.C.Accessed December 14, 2016. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003000458/PP/.

Sanderson, p.

How to Feed an Army at 152.

Ibid. at 105-6.

Sanderson, “Camp Fires and Camp Cooking” at 5.