“The Bloody Thirty First:" Reflections on the 31st Virginia Infantry at Allegheny Mountain

By Jason C. Spellman

Whilst we have abundant cause to thank God for this victory, let us not forget the gallant dead who fell by our sides, and whom we buried on Allegheny. Remember their gallantry, and emulate their example."

– Col. Edward Johnson, December 16, 1861

The 31st Regiment had not been strangers to the region. Men of Companies E and G had enlisted in Pocahontas County only seven months prior. Privates William and Henry Yaeger had quite literally found themselves defending their own farmland, which was located nearby. John Robson of the 52nd Regiment of Virginia Infantry recalled, “This regiment was mostly composed of Northwest Virginia men, and Milroy stood between them and home, which appeared to make them particularly severe on him, and their gallant commander, Major Boykin, led them with dauntless spirit” (Robson 21).

Gen. Robert H. Milroy (Library of Congress)

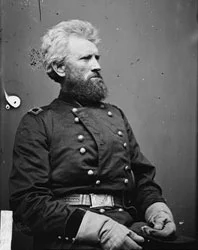

Col. Edward Johnson (West Virginia Archives and History)

The 31st Regiment had not been strangers to the region. Men of Companies E and G had enlisted in Pocahontas County only seven months prior. Privates William and Henry Yaeger had quite literally found themselves defending their own farmland, which was located nearby. John Robson of the 52nd Regiment of Virginia Infantry recalled, “This regiment was mostly composed of Northwest Virginia men, and Milroy stood between them and home, which appeared to make them particularly severe on him, and their gallant commander, Major Boykin, led them with dauntless spirit” (Robson 21).

For five months, the Federal forces under the command of General Robert H. Milroy, and the forces of the Confederacy,1 under General William W. Loring (commanded by Col. Edward Johnson) had camped within sight of each other. The Union advance had here been blocked and the summer and fall passed by with battles and skirmishes coordinated with exceptional effort by Milroy. Two smaller engagements had occurred in October but nothing as sizeable as the clash on top of Allegheny Mountain.

The Battle for Allegheny Mountain commenced on December 13, 1861. Around eight o’clock in the morning, Johnson’s Brigade was aroused by firing on the advance pickets.2 Colonel Johnson ordered the 31st Regiment to occupy an area near the Old Parkersburg-Staunton Turnpike located northeast of the military defenses above their winter campsite, Camp Baldwin. In The Diary of a Confederate Soldier, James Edmond Hall recalled that he almost froze while standing in field against the piercing wind. The 9th Virginia of Hansbrough’s Battalion had been immediately deployed but fell back and rallied with the 31st Regiment. Both then charged through the brush and poured forth a heavy fire onto the enemy. Fighting between Johnson and Milroy’s men3 was nearly hand-to-hand combat and tactically disorganized; hostility inflicted by both sides seemed to be equally damaging. An account by a Wheeling, W.Va. boy of the 2nd Virginia Regiment (U.S.) recalled, “Away we went whooping like devils, within two hundred yards of the rebel entrenchments, when the fire became so hot that all had to take shelter behind logs, trees and whatever else could be found. In this position we kept up a regular Indian fight for our four hours, towards the last the firing became so accurate that if an inch of one's person was exposed he was sure to catch it.” Hall despondently added, “Some of our best men fell – some of whom I had the strongest regard” (Ashcraft 24). Until Allegheny, neither side had ever witnessed such intense fighting before. By midday, the Federals had fallen back and taken cover but were preparing a defense.

Remains of cabins used by the 31st Virginia on Allegheny Mountain. (Roy Bird Cook Collection)

Still under fire, men of the 12th Georgia Regiment came in to support. One rebel observed, “Next, we attempted to turn the Union right but were immediately met and repulsed. But the Federals by this time had become more broken, but were again rallied by their officers, who conducted themselves nobly. We again came with the charge but again failed to route them” (Ashcraft 26). The Confederates tried to make an attempt to press the Federals from the woods but with little success. The enemy had instead anticipated its flanking strategy and attacked accordingly, driving them back to their winter cabins. But they retreated no farther after coming upon Colonel Johnson, who quickly rallied his men. Robson was in clear view of the fighting and became spellbound by his actions, “I remember how I thought Colonel Johnson must be the most wonderful hero in the world, as I saw him at one point, where his men were hard pressed, snatch a musket in one hand and, swinging a big club in the other, he led his line right up among the enemy” (Robson 21). Thus again, the attack was renewed and in large reinforcement. The Virginians and Georgians had been nearly out of ammunition but with great rejoice and ferocity, they stumbled forward with the Federals at face of their bayonets, inflicted severe casualties and took many prisoners.

First battery - top of Allegheny Mountain. (Roy Bird Cook Collection)

Five hundred of Johnson’s men continued to push an enemy twice larger a mile north towards the Cheat Mountain fort into the afternoon. The 31st Regiment was later repositioned to the defenses near the Green Bank Road and met a second Federal assault, during which they suffered heavy losses. In the end, they lost seven killed, thirty-six wounded, four mortally wounded, and eleven captured.4 In a report to the Assistant Adjutant-General, Colonel Johnson noted, “Major F. M. Boykin, Jr., commanding Thirty-first Virginia Volunteers, his officers and men, deserve my thanks for their unflinching courage throughout the struggle. This regiment suffered severely.” In actuality, they had suffered the highest casualties out of any Confederate regiment, earning them the reputation as, “The Bloody Thirty-First.” Reports published after the battle credited both sides with achieving victory. However, an honest opinion is best concluded by an Indiana soldier who wrote, “The truth is, the enemy defended their position with great valor, and at no period of the engagement did they show symptoms of deserting their post. Our attack was repulsed on both flanks, from the failure of the columns to begin the fight simultaneously, thus enabling the enemy to beat us in detail” (Stevenson). The aftermath of the battle had ended in Confederate victory but had come at a costly price.

The Battle of Allegheny Mountain was a turning point for the 31st Regiment. Reports of its courageousness and hard-earned service reached the ears of the Confederate high command. Assistant Adjutant-General John Withers issued Special Order No. 267 three days after the fighting which promoted Lt. Col. William L. Jackson (cousin of General Thomas J. Jackson) to colonel of the 31st Regiment. For his leadership and heroic action, Colonel Johnson was promoted to brigadier general of the Army of the Northwest and forever nicknamed Edward “Allegheny” Johnson, a changed reputation that he carried throughout the war. And, of course, the rather green young men of the regiment had become battle-hardened veterans a little more prepared for the oncoming months and engagements that lay ahead.

Equipage and Uniforms of the 31st Regiment in December of 1861

Proper supplies had been unavailable to the regiment from the beginning. When Company I was mustered into the 31st Regiment at Huttonsville in Randolph County on 8 June 1861, Major Francis M. Boykin noted, “Eleven men under command of the captain succeeded in getting possession of 40 of the old flint-lock rifles sent to Weston under cover of the night on June 2nd… A few have country rifles but no outfits of any kind” (Roy Bird Cook Collection). One veteran of Company D recalled, “I, with many of my fellow citizens of Gilmer County, gathered all available arms and ammunitions, which in the main consisted of a squirrel rifle, a few rounds of ammunition, sometimes a dirk knife, a revolver, or old fashioned revolver then known by the name of Pepper boxes” (Roy Bird Cook Collection). With initial constraints on issued clothing and equipment at the formation of the regiment, the men of the 31st were compelled to furnish their own goods from home, although, no doubt many of the initial weapons would have been replaced by December 1861.

While descriptive clothing records were reported for the first three years of the war, no direct inventory was documented during the winter. The sixth month commissary record, “Requisition for Clothing and Company Equipage” written on 26 August 1861, provides some insight on the general deficit of materials for the regiment. Reported clothing amongst the troops was as follows:

- Hats or Caps – 8 on hand; 652 required

- Coats – 11 on hand; 649 required

- Pants (pairs) – 24 on hand; 636 required

- Drawers (pairs) – 51 on hand; 1269 required

- Flannel shirts – 6 on hand; 1314 required

- Blankets – 625 on hand; 695 required

- Stockings (pairs) – 0 on hand; 1980 required

- Shoes (pairs) – 1 on hand; 1319 required

- Great Coats – 12 on hand; 648 required

- Knap Sacks – 268 on hand; 392 required

- Haver Sacks – 237 on hand; 423 required

- Canteens & Straps – 245 on hand; 417 required

Camp and garrison equipment were reported as follows:

- Axes & Hatchets – 5 on hand; 93 required

- Picks & Handles – 0 on hand; 68 required

- Spades – 0 on hand; 68 required

- Camp Kettles – 24 on hand; 74 required

- Common Tents – 102 on hand; 0 required

- Common Tent Poles or Pins – 102 on hand; 0 required

Two narrative accounts from members of the 52nd Virginia only seem to substantiate the lack of clothing and supplies requested months prior. John Robson of Company H describes the Confederate forces at Allegheny Mountain as equipped with “a scanty supply of blankets and rations” (Robson 20). In a December 9th letter to his wife, Henry H. Dedrick asks, “Dear Lissa I wrote to you to send me some pants the first chance you get and the rest of them that I wrote for as I am nearly out of pants.” Even weapons needed to be replaced. Fortunately, after the fighting on Allegheny Mountain, Colonel Johnson was able to secure about one hundred “stands of arms” which the Federals had discarded in the retreat.

A muster roll taken on 31 December 1861 describes the general character of the regiment: discipline, fair; instruction, indifferent; military appearance, fair; arms in good order; clothing, moderate supply. Efforts on the part of families and local communities to provide the regiment with goods show the extent of the shortages. In January 1862, Second Lieutenant James B. Galvin of Company I wrote to the Lutheran Sabbath School Association to thank the institution for providing them with fifty pairs of drawers. He writes, “They boys were very much in need of the kind considerations of the benevolent of Augusta County. The Lewis Rangers will long remember the kind esteem and gift…” (Roy Bird Cook Collection). Both before and after the Battle of Allegheny Mountain, the 31st Regiment was undergoing seriously clothing and equipment shortages that went unresolved for months.

Farmers Nooning (STAR Oil Painting Studio)

Cider Making (STAR Oil Painting Studio)

With the absence of military clothing, civilian dress was no doubt influenced by occupation. Statistics gathered by John Ashcraft provide some insight on the men of the regiment: from a 322-man sample, it was found that 68% were farmers, 4% attorneys, and 3% students (three largest groups). In looking at the majority, farming culture did not necessarily confine agrarian society to distinctive class dress. On the contrary, an article written for The Huntingdon Globe in November 1860 suggests that farmers of the day were perhaps being too fashionable instead of dressing conveniently. While the author does recommend overalls, thick-waterproof boots, red flannel shirts, knit shirts, etc., he likewise implies that men were dressing too formal for rather strenuous and active work. Early nineteenth century clothing that was being worn is best documented in the oil paintings of William Sydney Mount. Mount’s folk art depicts menswear consisting of vests, shirts, cravats, and occasional top hats as worn by farming communities. Individual occupation no doubt influenced an individual’s daily dress, and in particular, nineteenth century agrarian societies did not fully dress in attire that was both fashionable and convenient.

Footnotes

About 1,200 men, consisting of the 12th Georgia, 31st Virginia, the 52d Virginia under Colonel Baldwin, the battalions of Hansborough and Riger, and two batteries of four 6-pounders under Captains Anderson and Miller, also one company of cavalry under Captain Flournoy […]” (Robson 20).

One Federal account explains, “The object of the expedition was explained to us, it being to clean out Camp Baldwin, situate on top of the Alleghany mountains, distant from [Camp] Cheat Mountain Summit about twenty five miles” (Wheeling Intelligencer).

25th and 32nd Ohio, 9th and 13th Indiana, 2nd Virginia Regiments

Ashcraft uses these figures in his account of the battle but totals the battle losses in his statistics report (p. 110) as being fifty-three casualties on December 15, 1861.

Works Cited

Ashcraft, John M. 31st Virginia Infantry. 1st ed. Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1988.

“The Battle of Allegheny Summit: Full Account from one of the Wheeling Boys who was in it.” Wheeling Intelligencer, December 24, 1861.

West Virginia Archives and History. 15 June 2009 <http://www.wvculture.org/history/civilwar/alleghenymountain02.html>.

“The Battle of the Top of the Allegheny on December 13, 1861.” West Virginia Legislative Hand Book, 1928. West Virginia Archives and History. 17 June 2009 <http://www.wvculture.org/hiSTory/civilwar/alleghenymountain01.html>.

Brady National Photographic Art Gallery (Washington, D.C.), photographer. Portrait of Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy, officer of the Federal Army (Maj. Gen. from Nov. 29, 1862). LC-DIG-cwpb-04624. 1860-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 23 June 2009 <http://lcweb2.loc.gov/>.

Colonel Edward Johnson and General Robert Milroy. West Virginia Archives and History, Charleston. 24 June 2009 <http://www.wvculture.org/HiStory/thisdayinwvhistory/1213.html>.

Cook, Roy Bird. Roy Bird Cook Collection: Documents of the 31st Regiment (CSA). West Virginia History Online Digital Collections. West Virginia and Regional History Collection. 1 June 2009 <http://www.libraries.wvu.edu/Roy_Cook_JPG/>.

“Dedrick Civil War Letter, 1861 December 9.” Henry H. Dedrick Papers. VMI Archives and Online Historical Research Center. Virginia Military Institute. 25 June 2009 <http://www.vmi.edu/archives.aspx?id=11541>.

“Farmers’ Clothes.” The Huntingdon Globe 28 November 1860: 1.

Francis M. Boykin Civil War Papers. 31st Virginia Infantry Regiment. VMI Archives and Online Historical Research Center. Virginia Military Institute. 1 June 2009 <http://www.vmi.edu/archives.aspx?id=6783>.

Hall, James E. The Diary of a Confederate Soldier. Ed. Ruth Woods Dayton. Lewisburg, W.Va., 1961.

Johnson, Edward. “Battle of Allegheny Mountain.” Official Records. Vol. 5. West Virginia Archives and History. 26 June 2009 <http://www.wvculture.org/HiStory/civilwar/alleghenymountain03.html>.

Mount, William Sydney. Farmers Nooning. 1836. Museums of Stony Brook, Stony Brook. 25 June 2009 <http://www.staroilpainting.com/p_18224.htm>.

Mount, William Sydney. Cider Making. 1840-41. Museums of Stony Brook, Stony Brook. 25 June 2009 <http://www.staroilpainting.com/p_1487.htm>.

Robson, John S. How a One-Legged Rebel Lives: Reminiscences of the Civil War. Durham: The Educator Co. Printers and Binders, 1898.

Stevenson, David. Indiana's Roll of Honor. Vol. 1. Indianapolis: A. D. Streight, 1864.