Support for Support Arms

By Marc A. Hermann

One of the first things that every military reenactor learns to master is, by necessity, the manual of arms. Whether the person decides to pursue a mainstream or progressive approach to Civil War re-enacting, almost everyone makes a concerted effort to learn the correct way to carry and use the long arm appropriate to his portrayal. The new recruit of today, as his counterparts of 1861, will usually learn this choreography from a senior member of his unit in the context of a squad or company drill, and later may (and is advised to) study the original books for himself to make sure that all the nuances of each position are there when he executes them.

Unfortunately, much is lost over 140 years, and without going back to those primary sources, a hapless "recruit" of the 21st century may get into the habit of doing things the wrong way, simply because it was taught to him by a seemingly knowledgeable N.C.O., who himself has had it ingrained since he started re-enacting 20 years before. We are creatures of habit, and sometimes reject the notion of change, and may even take it as a personal affront if corrected about something that is historically inaccurate. We need to get beyond this, though. There is an issue that transcends all aspects of the living history community, from those who have the worst impressions to those who have the best impressions -- I have seen it everywhere.

I am referring to the position of "Support Arms."

"Stop doing the British manual!"

No one likes the smart alecky private who, in the middle of company drill, whips out a manual from his pocket and loudly corrects a command just given by his officer. It is bad etiquette, and borderline disrespectful. However, what happens when the officer IS, in fact, wrong? What happens when one man in a company executes a command as he interprets it from the manuals, but the other 19 men do it as their trustworthy Captain has taught them to do it? Such an issue arose at a recent parade that I attended with my friend, Jason Wickersty. Standing near each other in line, we noticed a distinct difference between the positions of our weapons compared to those of the others when our company was ordered to "Support Arms." Namely, our weapons were being supported in such a manner that they were nearly perfectly vertical, and our left hands resting near the bottom of our rib cages.

Suddenly, the booming voice of the Sergeant from the right flank of the company admonished "Hey! Stop doing the British manual, and put some tilt in your rifle like everyone else!"

Jason and I exchanged shocked glances. Here we were, executing a maneuver in a manner based on not only the original (and, incidentally, NOT British) manuals, but on photographic evidence -- and WE were the ones being scolded! From that point on, I have made it my business to enlighten anyone who cares to listen about the correct position of Support Arms.

Margin of error?

The story of infantry tactics during the American Civil War is one of adaptation, of officers and men learning to think for themselves in order to become better soldiers. The maneuvers of light infantry to keep an enemy in check and the crushing blows of frontal assaults to break through a fortified position were the results of trial and error, and re-examination of the military manuals as published. One is correct to assume that soldiers didn't ALWAYS follow the books to the letter, but that does not give one carte blanche to do whatsoever he may please when demonstrating 19th century tactics -- particularly when one considers that an average soldier spent literally hours daily at drill, and the average reenactor spends a matter of hours per year at it. So first, we read the books and try to master the drill as written. Then, the more practical among us, in our search for enlightenment, will look at original photographs to see how the soldiers interpreted the manuals. Are period photographs reliable, though? Any student of 19th century images knows that subjects were often carefully posed. Therefore, to determine if something we see in a picture was truly done as we see it being done, then we must work with a wide control group, that shows soldiers in all contexts and regions. If it can be determined that something wasn't just a local fad or the act of an individual wishing to cut a perfect image for posterity, and is also seen being executed by those who may not even have been aware an image was being made, then we can safely deduce that it was widely practiced. In addition, one might even detect slight variations, but they do not deviate as far from the perceived "correctness" as modern reenactors have, thus giving them even more credence by acknowledging that while variations certainly did exist, they were not as grossly varied as we may explain away our executions of them.

The position of Support Arms, as phrased in all the leading manuals in use during the Civil War, both North and South, is almost universal.

Gilham's Manual

Gilham's Manual of Instruction (1860)

Support - ARMS.

One time and three motions.

143. First motion. Bring the piece, with the right hand, perpendicularly to the front and between the eyes, the barrel to the rear; seize the piece with the left hand at the lower band, raise this hand as high as the chin, and seize the piece at the same time with the right hand four inches below the cock.

Second motion. Turn the piece with the right hand, the barrel to the front; carry the piece to the left shoulder, and pass the fore-arm extended on the breast between the right hand and the cock; support the cock against the left fore-arm, the left hand resting on the right breast.

Third motion. Drop the right hand by the side.

Baxter's Manual

Baxter's Volunteer Manual (1861)

1. Support. 2. ARMS.*

One time and three motions.

(First motion.) At the command arms raise the piece with the left hand (elbow bent) about four inches, without turning the piece-at the same time with the right hand seize the small of the stock, thumb under and against the shoulder of the lock, fingers closed and against the out-side of the small or handle.

(Second motion.) Quit the butt with the left hand; place the left fore-arm under the hammer, the little finger on top of and resting on the body belt, hand opposite to the centre of the body; the weight of the musket resting on the fore-arm near the wrist, and the piece perpendicular.

(Third motion.) Drop the right hand by its side and the position is complete.

* NOTE: Baxter's manual utilized the "older" style of Shouldered Arms with the left hand.

Hardee's Revised

Hardee's Revised Rifle & Infantry Tactics (1862)

1. Support. 2. ARMS.

One time and three motions.

133. (First motion.) Bring the piece, with the right hand, perpendicularly to the front and between the eyes, the barrel to the rear; seize the piece with the left hand at the lower band, raise this hand as high as the chin, and seize the piece at the same time with the right hand four inches below the cock.

134. (Second motion.) Turn the piece with the right hand, the barrel to the front; carry the piece to the left shoulder, and pass the fore-arm extended on the breast between the right hand and the cock; support the cock against the left fore-arm, the left hand resting on the right breast.

135. (Third motion.) Drop the right hand by the side.

Casey's

Casey's Infantry Tactics (1862)

Support - ARMS.

One time and three motions.

140. (First motion.) Bring the piece, with the right hand, perpendicularly to the front and between the eyes, the barrel to the rear; seize the piece with the left hand at the lower band, raise this hand as high as the chin, and seize the piece at the same time with the right hand four inches below the cock.

141. (Second motion.) Turn the piece with the right hand, the barrel to the front; carry the piece to the left shoulder, and pass the fore-arm extended on the breast between the right hand and the cock; support the cock against the left fore-arm, the left hand resting on the right breast.

142. (Third motion.) Drop the right hand by the side.

Please note the straightness of the piece in all examples. Also note in the side view from Baxter's the position of the stock in relation to the left thigh -- it is parallel to it, and does not protrude forward. In addition, the left hand never goes higher than the right breast. Somehow, this has evolved into the reeenactor's version of Support Arms:

The rifles are being carried on near 45-degree angles, and the left hand is resting above the right collarbone. How many times have you seen this done at re-enactments?

The author pictured in a parade at the correct position of Support Arms.

Taking it to the Field

Using the argument stated before, that soldiers didn't always do exactly what the manuals stated, might it stand to reason that, in reality, Support Arms during 1861-1865 may well have looked like that of our modern comrades? Not exactly. Below are selected images from the Library of Congress, showing Support Arms as it was done by the people we attempt to portray.

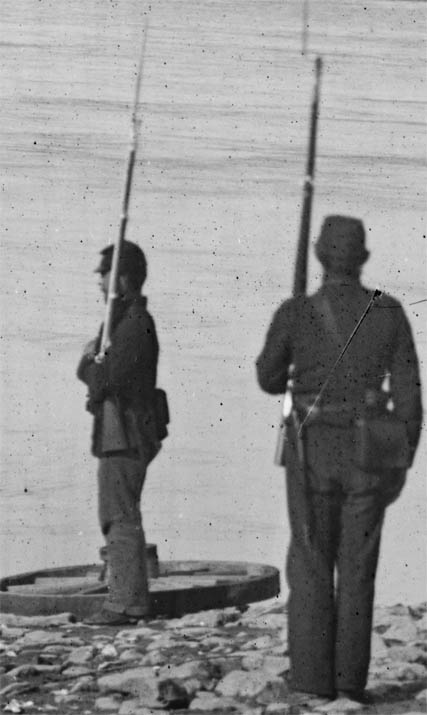

When viewed from the front, one can most clearly see the position of the soldier's left hand -- it is never higher than the breast. The second soldier appears to have it as low as his abdomen. Also note how straight and vertical the piece is carried in each instance -- it is not listing towards the rear. This is further illustrated in the next set of images.

In the first two images, when viewed from the rear, we can see that the rifle is not resting at all on the top part of the man's shoulder. In the third and fourth images, we can see this even clearer -- all the "support" occurs at the small of the stock and the left breast. This will cause the piece to rest in a straight manner. When the soldier is viewed from the right, as in the fifth image, the stock should not be visible forward of the hips. If the 1st Sergeant were to look down a line of men at support arms, he should not see one rifle stock protruding to the front.

Conclusion

Some years ago, Cal Kinzer wrote an article titled "A Dozen Inexpensive Ways to Improve Your Personal Impression" which contained tips on how to present a better soldier's portrayal without burning a hole in your checkbook. To this list of twelve, I would like to submit that spending quality time reviewing the manuals for little details you may have missed, and reviewing photographs showing how these manuals were put into practice are one of the biggest (and cheapest) steps a reenactor can take in the quest to "be like them." Likewise, re-enacting officers would be best advised to drop the arrogance of "I've been doing this since the '70s, there's nothing new you can teach me" and go back to the basics, and encourage their men to do the same. Just as in the game "Telephone," the quality of the information diminishes the further away from the original source it gets, such that decades of reenactors learning from reenactors results in the folks of our hobby looking like just that -- hobbyists. There are no better teachers of tactics than those who authored and mastered them in the 19th century. Their writings, drawings, and photographs are readily available. Use them!

Federal soldiers at the Elk River Bridge, Tennessee, 1862.

Soldiers in the crowd at the Grand Review, 1865, showing slight degrees of variation among individuals, though staying somewhat true to the manual.

26th New York at Fort Lyon, Va.

Sources

Baxter, Col. D. W. C. The Volunteer's Manual. Philadelphia: King & Baird, 1861.

Casey, Brig. Gen. Silas. Infantry Tactics. New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1862.

Gilham, Maj. William. Manual of Instruction. Philadelphia: Charles Desilver, 1860.

Hardee, Brig. Gen. W. J. Rifle and Infantry Tactics. North Carolina: 1862.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs.

Stillwagon, John. Right Shoulder, Shift: A Reexamination. Southern Guard Living History Association.

Special thanks to: Amanda Bradley, Bo Carlson, Ed Hermann, and Jason Wickersty.

This article may be distributed freely, but credit to the author must be given.